McDonald’s isn’t burgers. Starbucks isn’t coffee. Google isn’t tech.

Why the world's most iconic firms are landlords, banks, and ad machines in disguise

More fiction has been written in Excel than in Word.

—Morgan Housel

Things are not always what they seem; the first appearance deceives many; the intelligence of a few perceives what has been carefully hidden.

—Phaedrus

Apollo Robbins’ TED talk, The Art of Misdirection, is well worth your time. Robbins—by trade, a pickpocket, but not the kind you find on subways—shows how easily our attention is stolen. Not by elaborate tricks, but by a subtle shift of focus:

He reminds us that we see a lot, but we take in very little.

That lesson scales. Far too often, we take companies at face value: tech builds tech, restaurants sell food, airlines fly planes. But companies, like pickpockets, practice misdirection every day. They present one thing up front—the pizza box, the airplane seat, the streaming app—while the real profit engine hums behind the curtain.

Publicly traded companies legally have to provide you with these answers. However, far too often individuals don't know where to find them. If you pay close attention to the footnotes, the financial statements, and the margins buried in 10-Ks and 10-Qs you’ll see many iconic firms are really something else entirely.

What we buy, what they sell, and what they monetize are seldom the same thing

Below is a field guide. Every entry follows the same map: what they look like, what they really are, and the numbers that give them away.

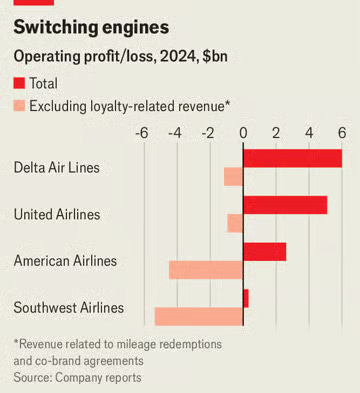

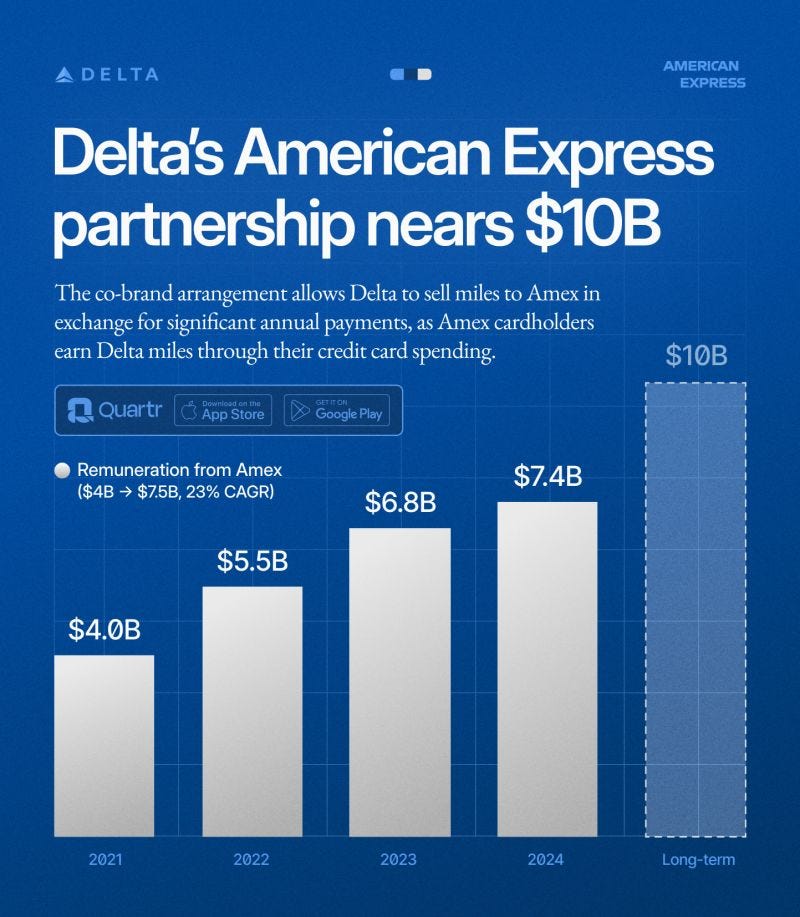

Airlines: Financial-engineering firms that operate jets

Looks like: people movers

Is actually: loyalty-program bankers

Receipts: Delta’s 10-K highlights its American Express partnership as a major earnings stream; United and American collateralized loyalty programs for billions during COVID

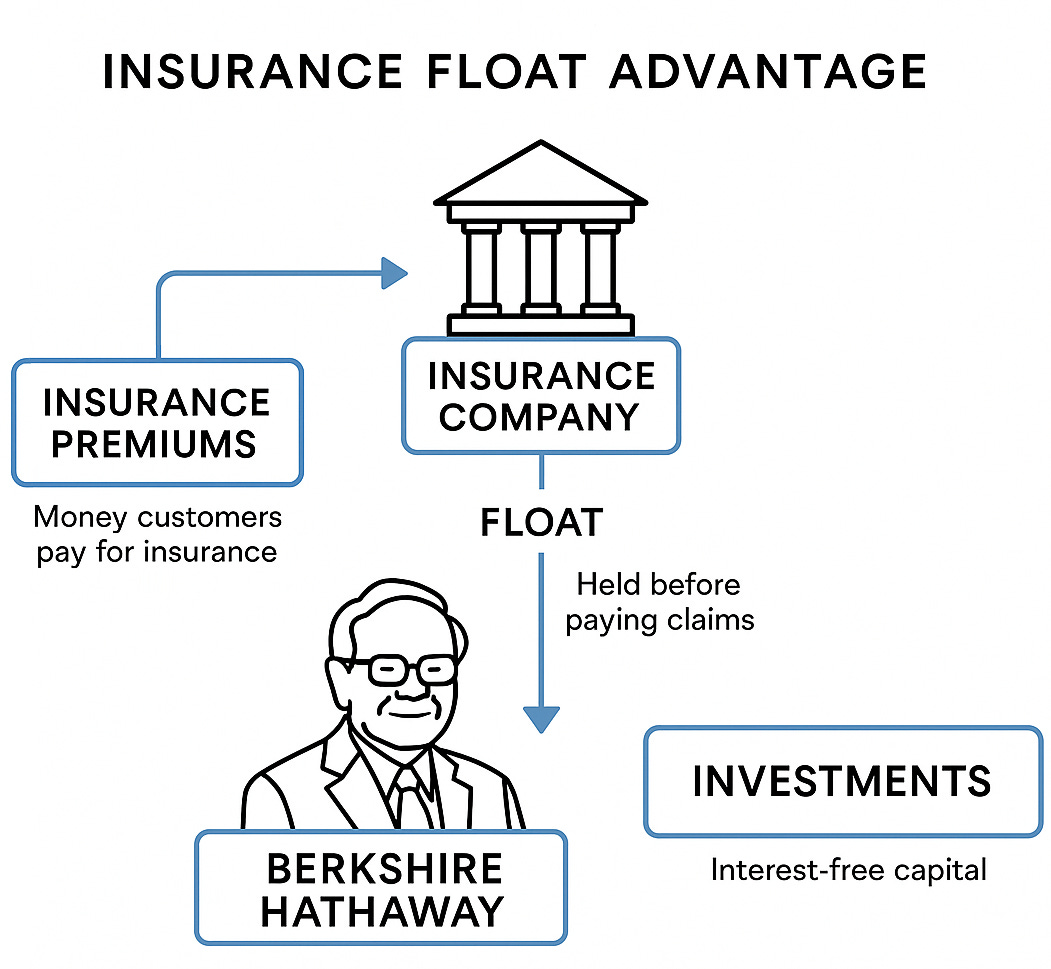

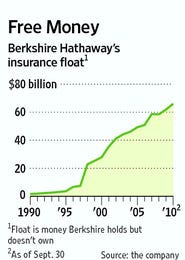

Berkshire Hathaway: An investment company powered by insurance float

Looks like: a conglomerate

Is actually: an asset allocator funded by insurance float

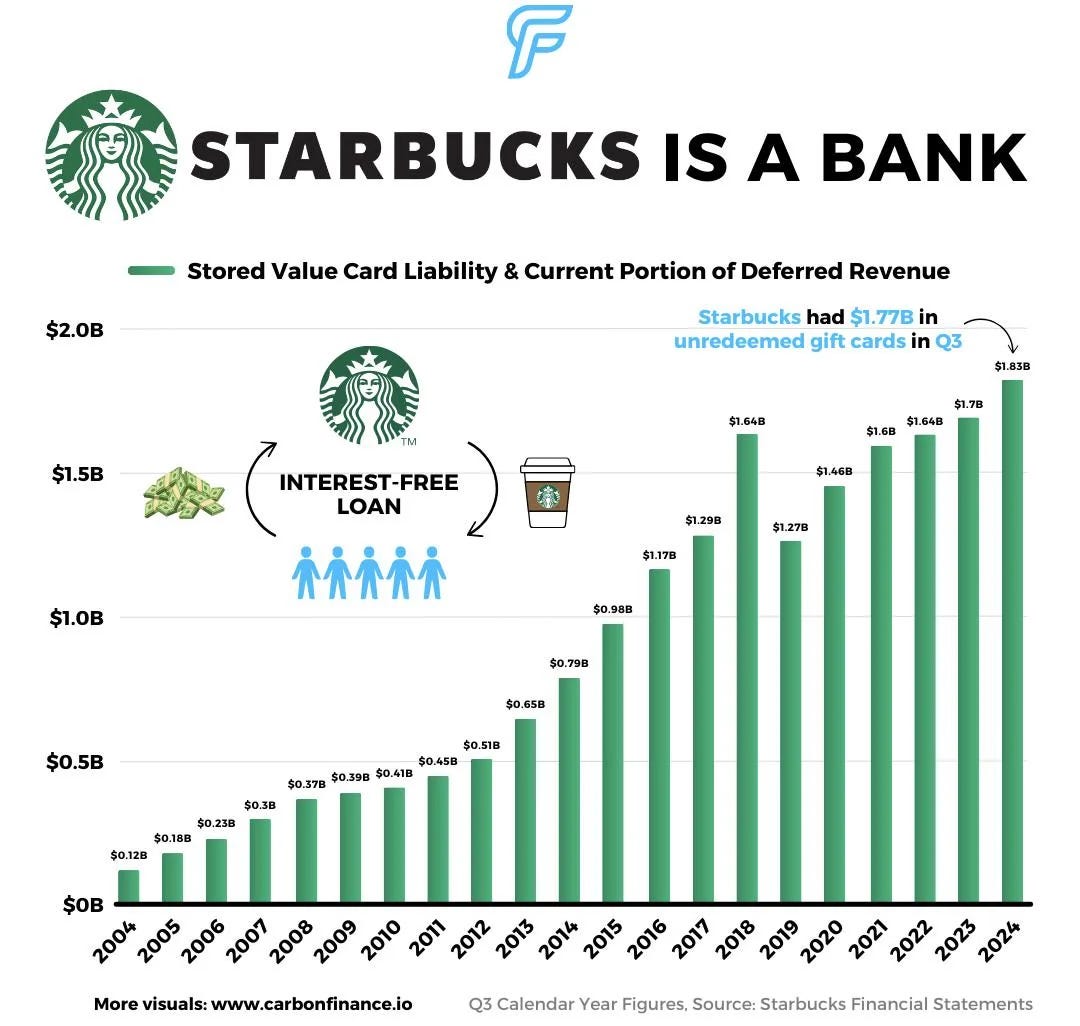

Starbucks: A café with a stored-value float

Looks like: a global coffee chain

Is actually: a café that runs on an enormous, interest-free stored-value float from gift cards and app balances

Receipts: Starbucks shows “stored value card liability” in the billions—capital Starbucks can use before delivering a latte

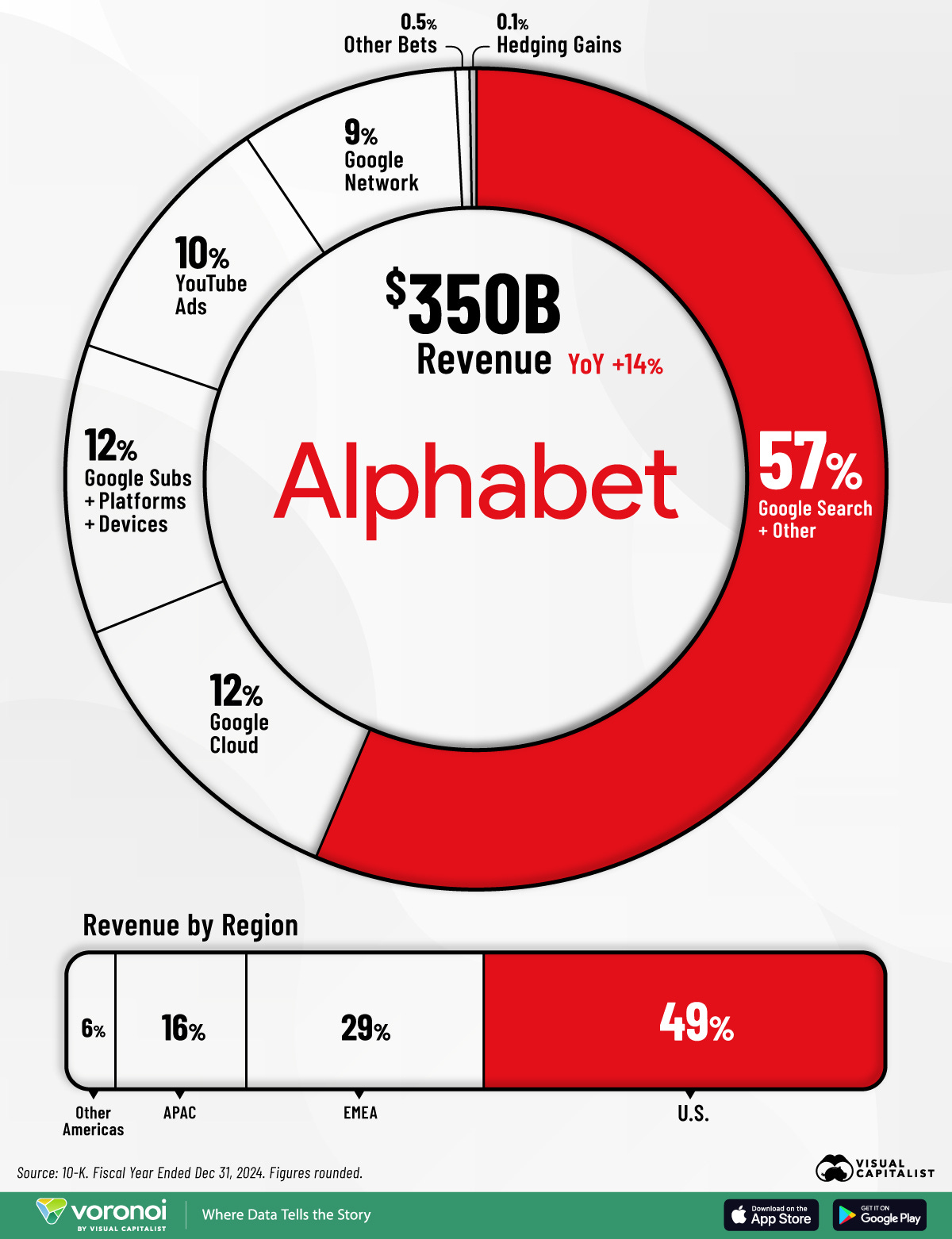

Google/Alphabet: An advertising company that makes technology

Looks like: a frontier AI/cloud giant

Is actually: an ad machine with unparalleled distribution

Receipts: Alphabet’s 2024 10-K shows Google advertising still dominates, dwarfing Cloud and “Other Bets”

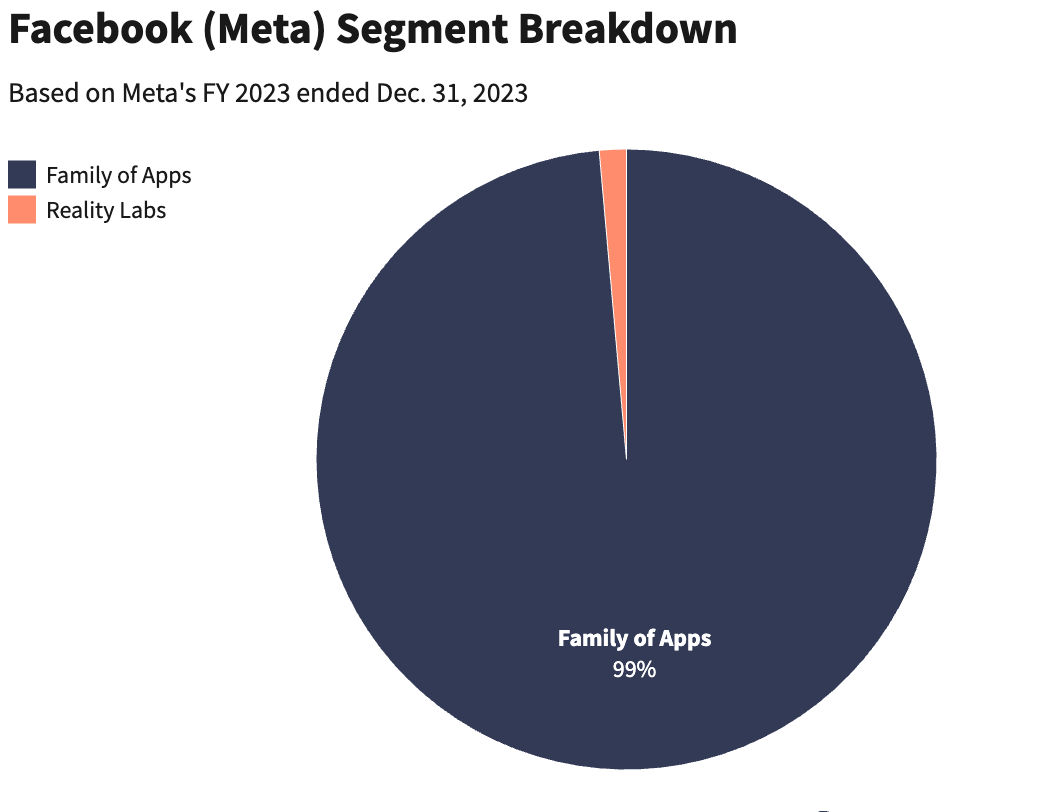

Meta: An advertising company with social apps attached

Looks like: a social/VR pioneer

Is actually: a paid attention broker

Receipts: In 2023, about 99% of Meta’s revenue was advertising

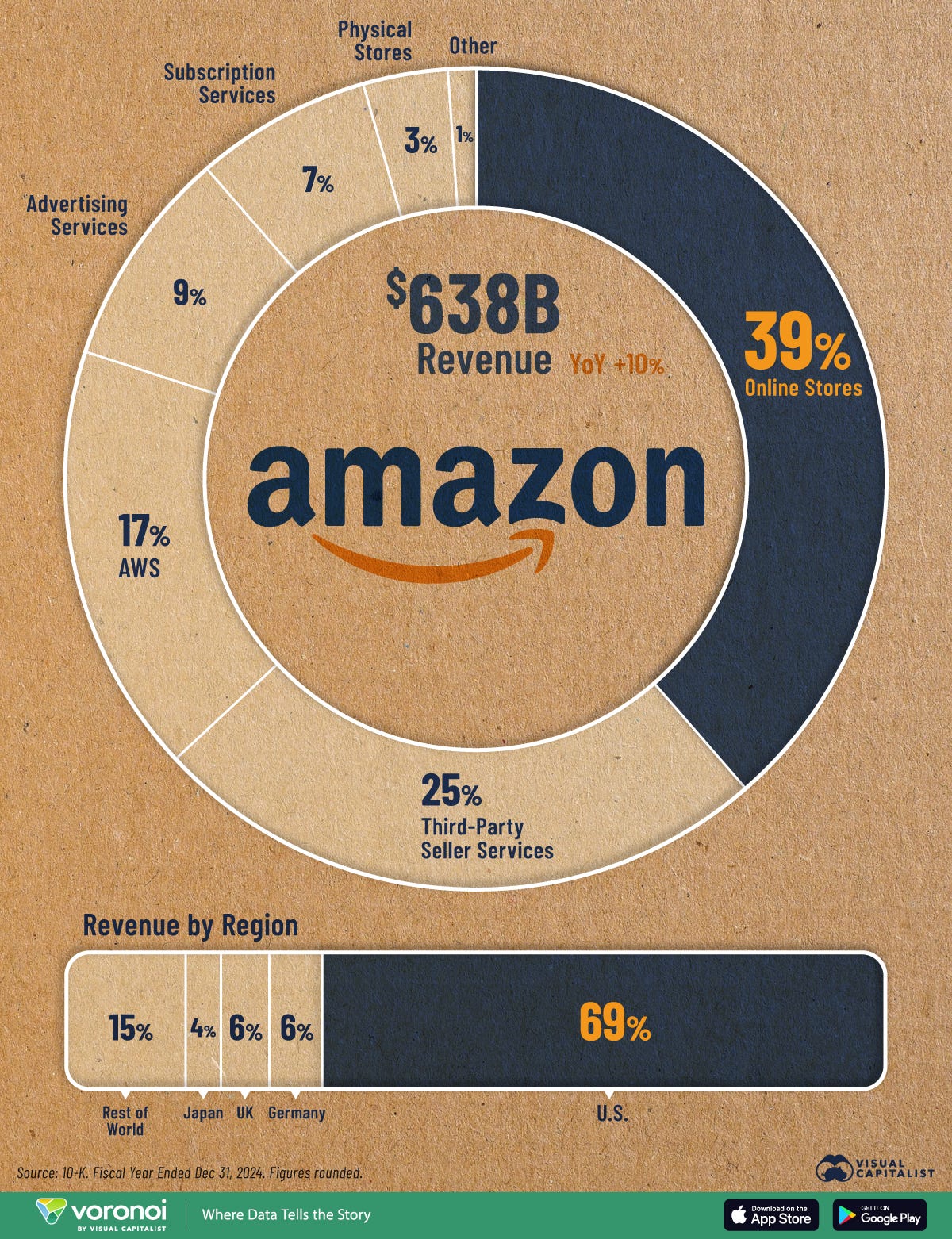

Amazon: A membership club that offers logistics + ads + a cloud conglomerate

Looks like: an e-commerce retailer

Is actually: a logistics utility, an ads network, and a profit engine named AWS

Receipts: AWS brought in $90.8B in 2023 with ~27% operating margin; ad services reached $47B

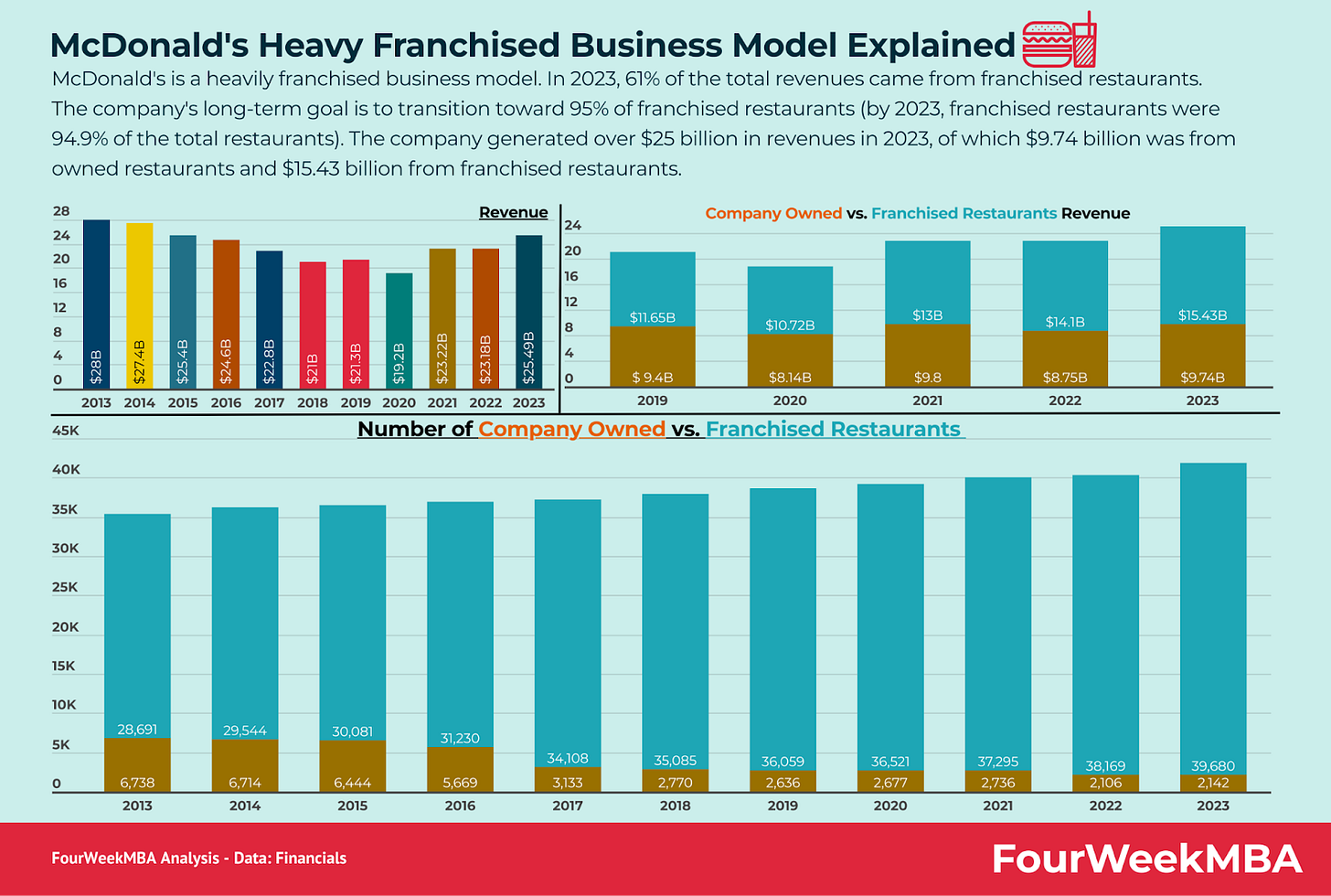

McDonald’s: A real-estate company disguised as fast food joint

Looks like: a burger chain

Is actually: a landlord with tenants

Receipts: McDonald’s 2023 10-K explains franchisee revenue is primarily rent and royalties; former McDonald’s CFO Harry J. Sonneborn famously quipped, “We are not technically in the food business. We are in the real estate business. The only reason we sell 15-cent hamburgers is because they are the greatest producer of revenue, from which our tenants can pay us rent.”

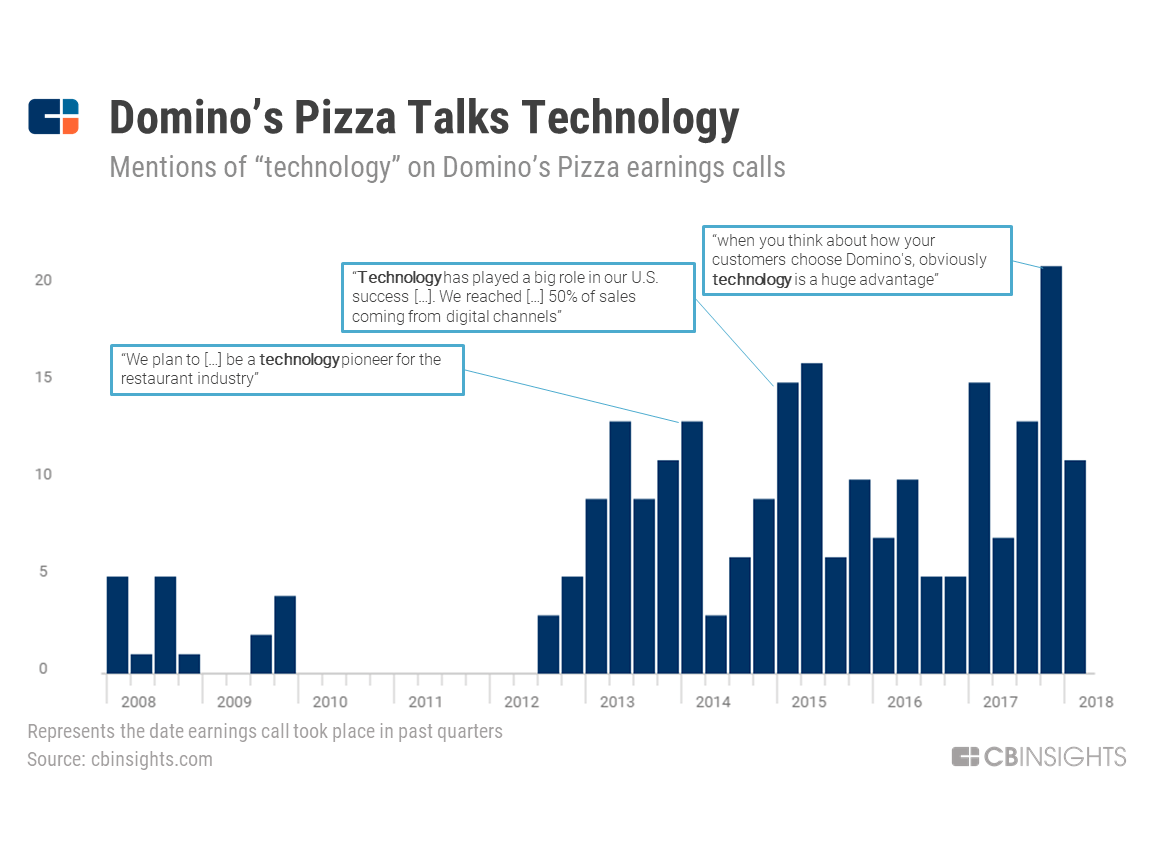

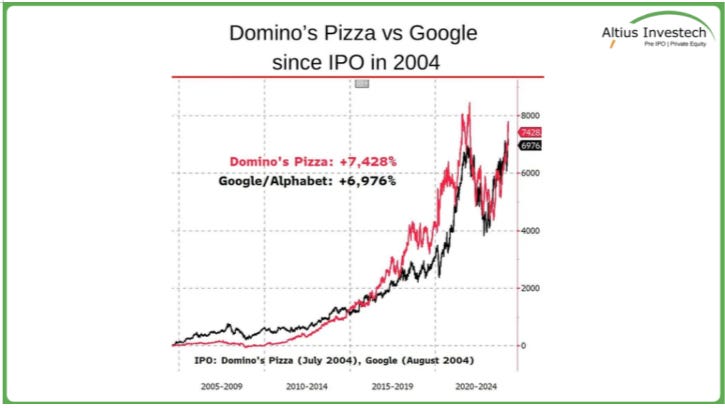

Domino’s: A technology company that makes pizza

Looks like: quick-service restaurants

Is actually: a digital logistics platform

Receipts: Over 80% of global retail sales came through digital ordering in 2023; back in 2018, former CEO J. Patrick Doyle called his shot: “Fundamentally, we are on a path to take all orders digitally. Doing so will mean not only a better customer experience, which should generate continued sales and store-level profit growth, it allows our store-level teams to focus all their efforts on making great pizzas and giving great service to our customers.”

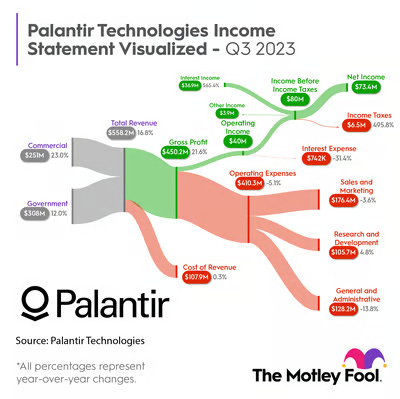

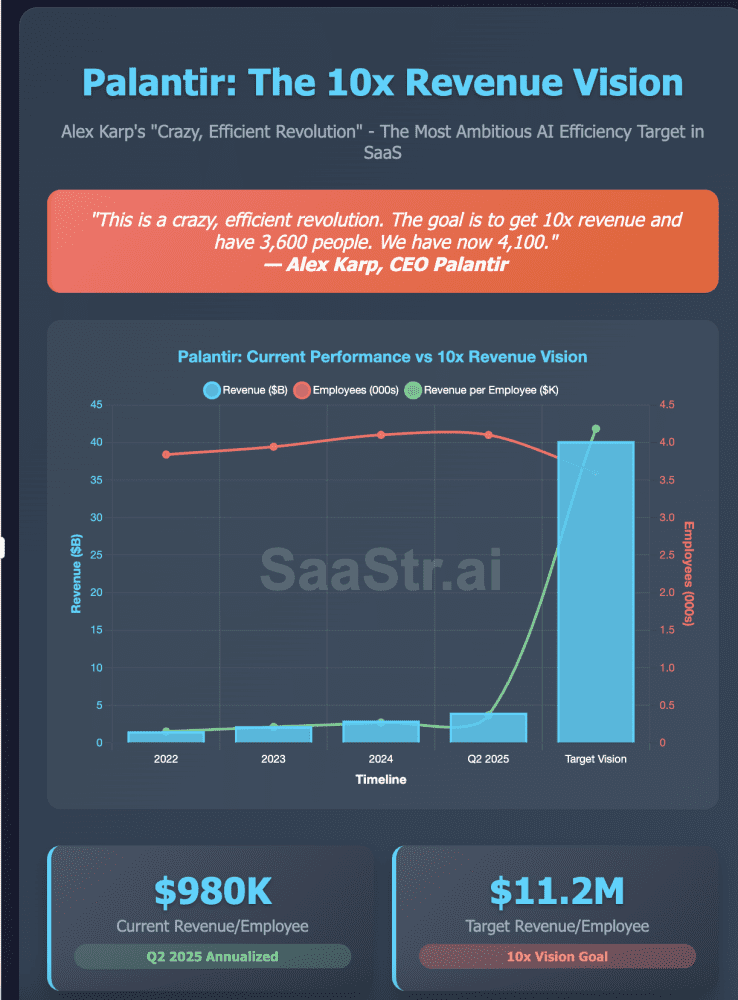

Palantir: A productized AI consultancy

Looks like: a pure software vendor

Is actually: hybrid software + embedded services, especially for government

Receipts: Palantir’s 2023 10-K shows revenue split between subscriptions and professional services. However, over time (much like Netflix) Palantir's goal is to cannibalize itself

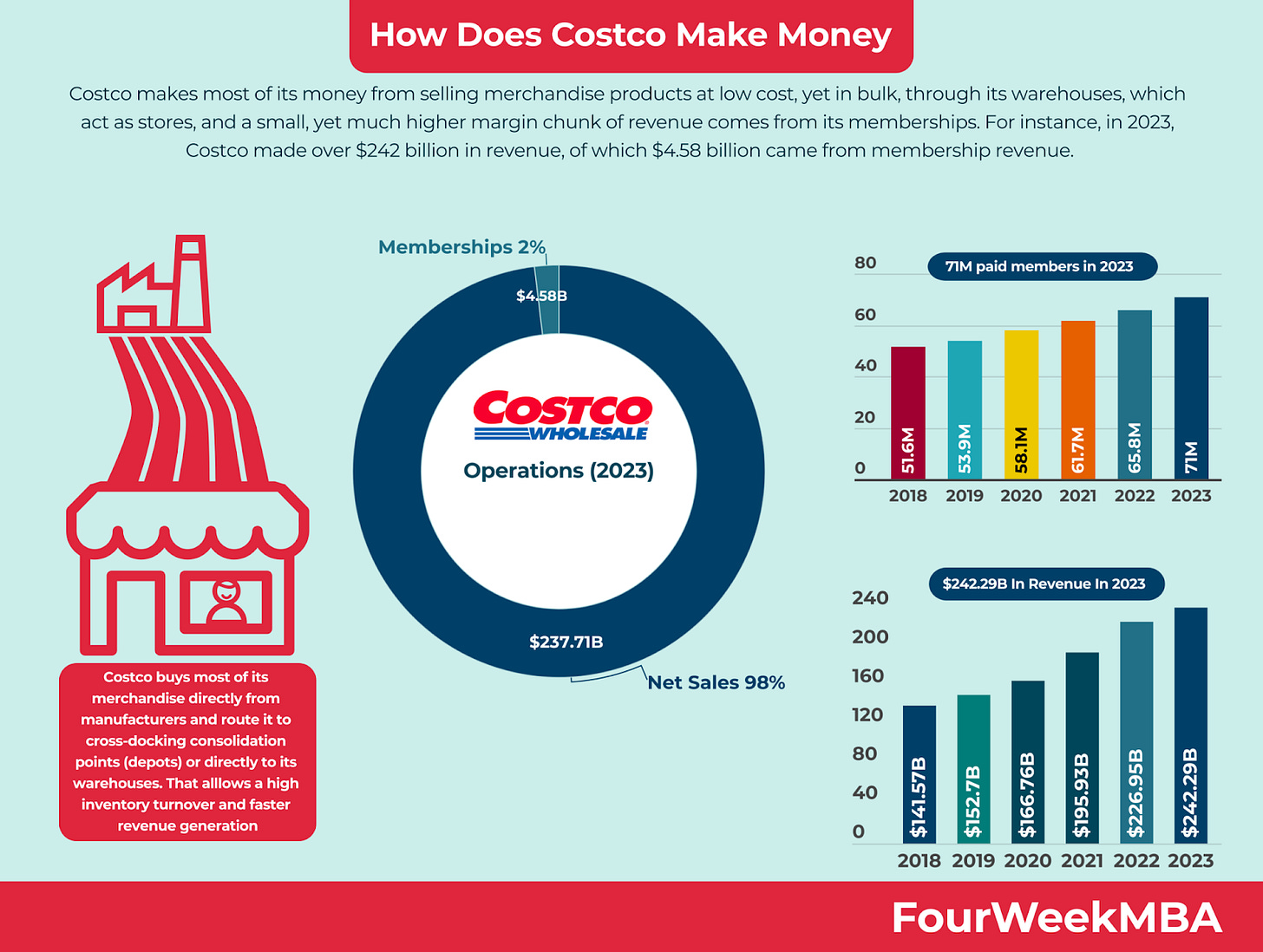

Costco: A membership company that sells groceries at cost

Looks like: a warehouse retailer

Is actually: a subscription club

Receipts: Membership fees contributed ~$4.8B in 2024—pure high-margin profit

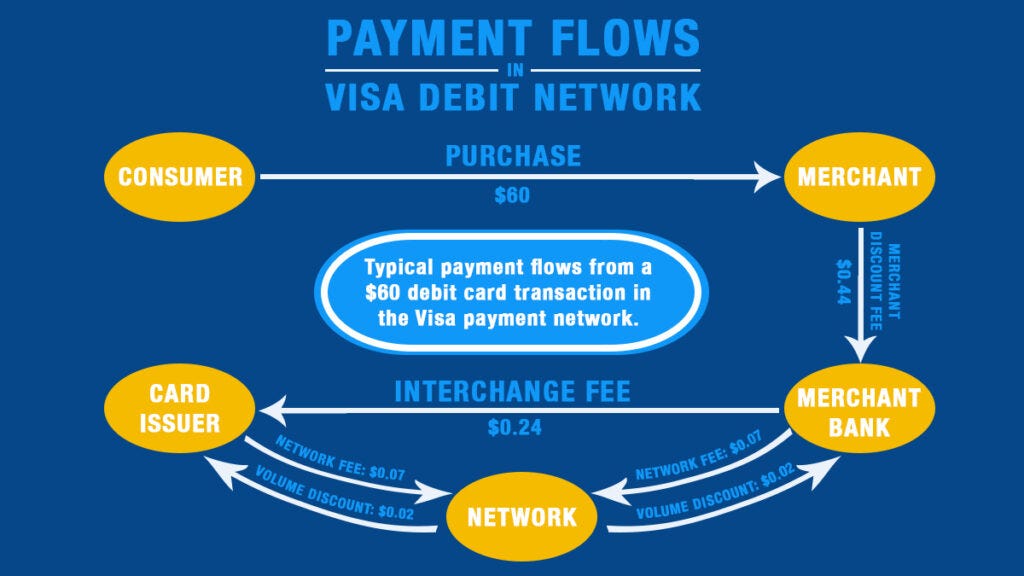

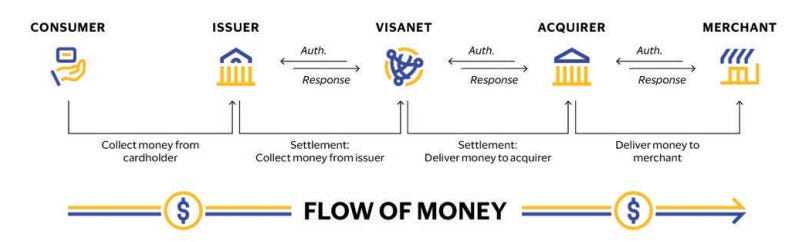

Visa & Mastercard: Toll roads, not lenders

Looks like: credit card companies

Is actually: global transaction networks

Receipts: Visa’s 10-K clarifies they don’t issue cards or set interest rates; they levy network fees

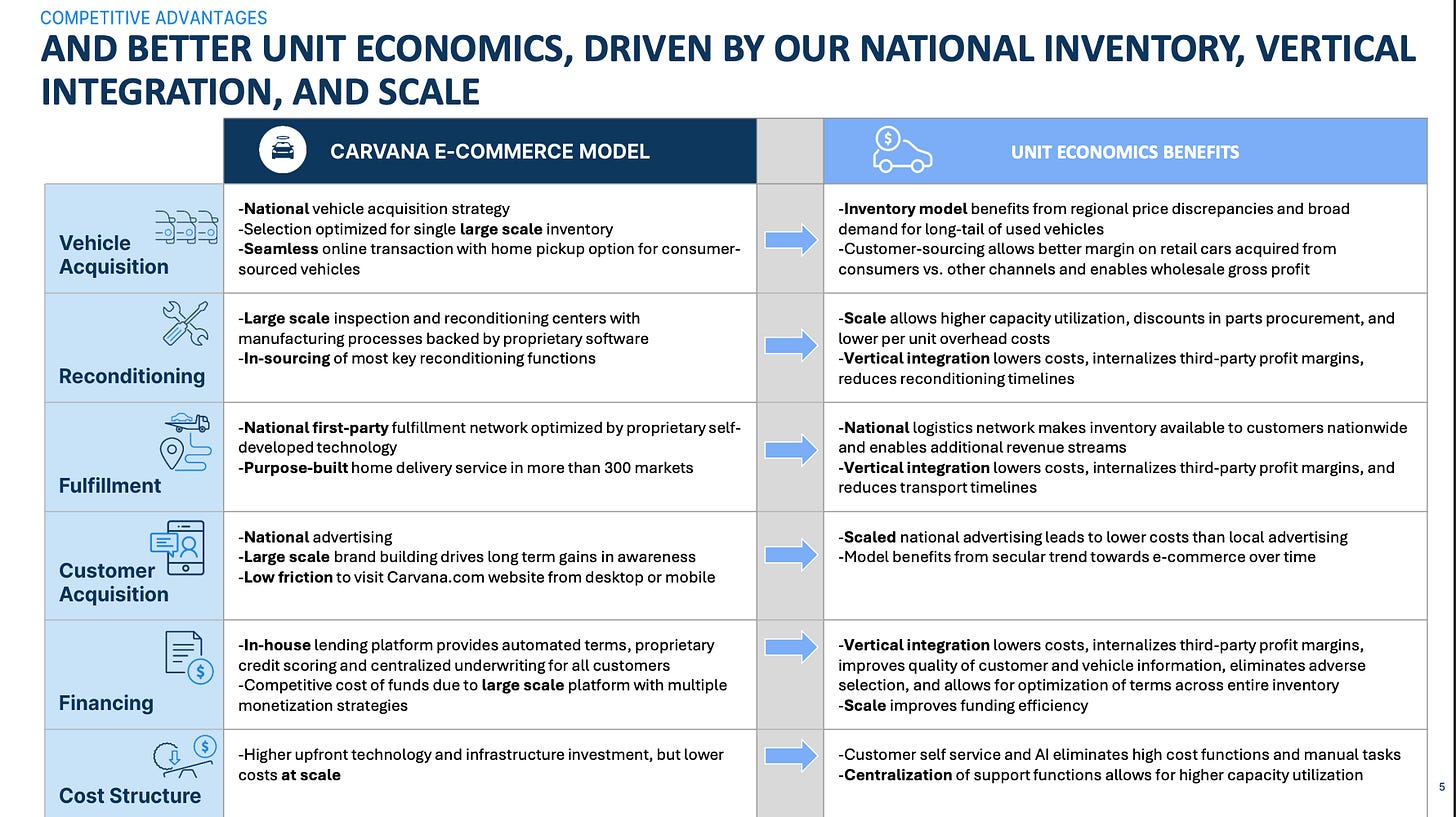

Carvana: A finance company with a used-car front end

Looks like: an online dealer

Is actually: a loan securitizer

Receipts: Carvana regularly sells auto loans into securitizations; see its differentiated business model (presented for investors) here

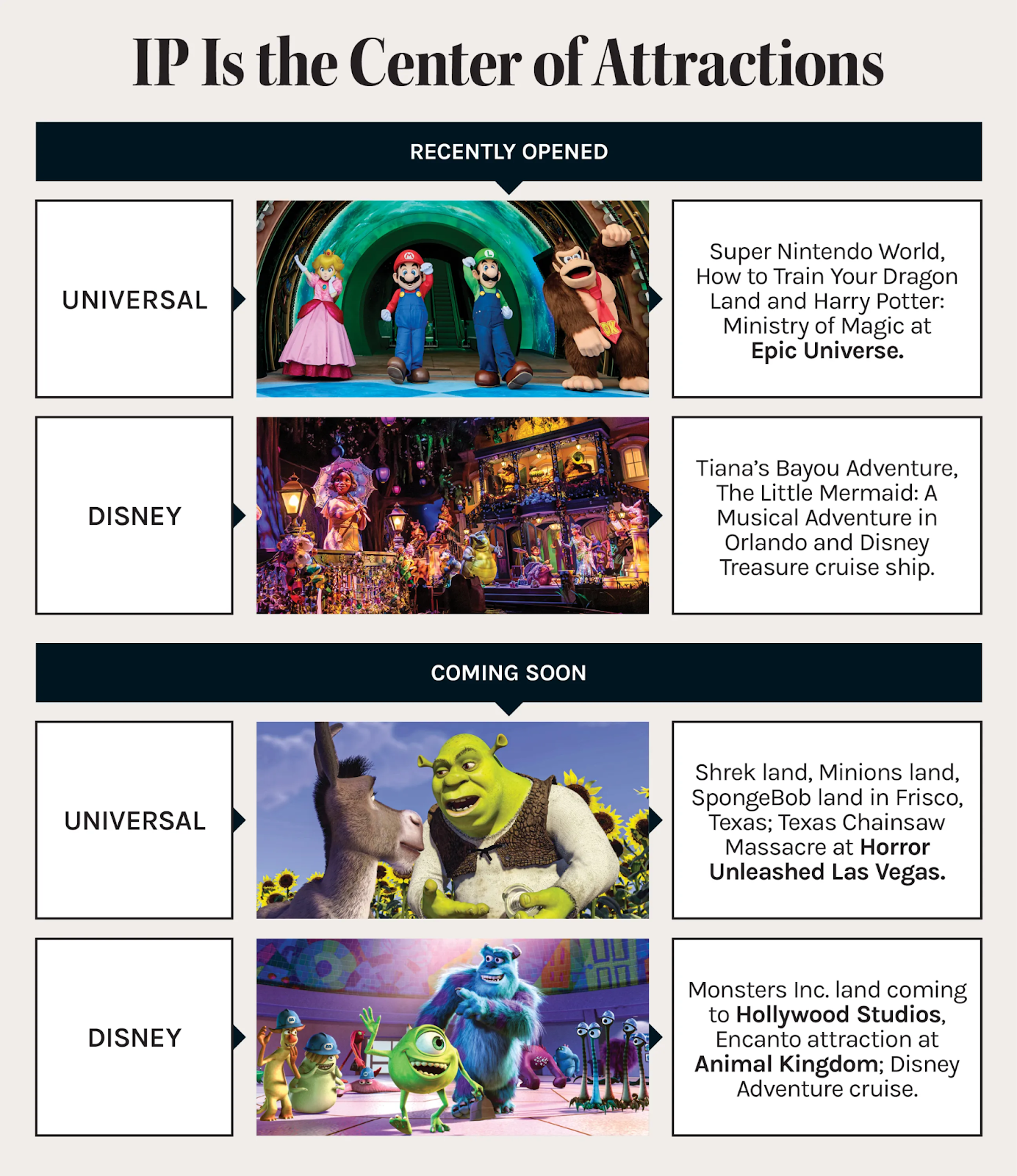

Disney: An IP utility that also makes movies

Looks like: an entertainment studio

Is actually: a parks & experiences empire

Receipts: Disney’s 2023 Annual Report shows Parks/Experiences as its most profitable segment

How to spot a business hiding in plain sight

Follow the margins. The highest-margin line usually reveals the true business (e.g. AWS, membership fees, ad units)

Read “Other” lines. “Other income,” “deferred revenue,” “breakage,” “network fees,” and “securitizations” often carry the story

Check segment reporting. Where segment operating income clusters tells you where the power lives

Watch the cash. Recurring, high-margin cash (subscriptions, fees, loyalty payments) funds the visible, low-margin stuff (planes, pizzas, parcels)

Footnotes are your friends. Companies often bury the most revealing details in the notes, not the headlines

If you’re a builder: copy the hidden engine, not the glossy paint job.

If you’re an investor: underwrite the real business model.

If you’re a consumer: understand the incentives shaping your feed, fare, and fries.

No matter who you are—builder, investor, consumer—remember: the trick isn’t in what’s shown to you, but what you fail to notice.

Keep your eyes peeled and your wallets ready—caveat emptor!

Per my about page, White Noise is a work of experimentation. I view it as a sort of thinking aloud, a stress testing of my nascent ideas. Through it, I hope to sharpen my opinions against the whetstone of other people’s feedback, commentary, and input.

If you want to discuss any of the ideas or musings mentioned above or have any books, papers, or links that you think would be interesting to share on a future edition of White Noise, please reach out to me by replying to this email or following me on Twitter X.

With sincere gratitude,

Tom

Amazing insights and a great read. Thanks for sharing Tom.

Speaking of Starbucks’ gift cards, I am always amazed, when I rummage through my kitchen doors, or my wallet, months post-facto, how many unused gift cards occupy the space. Between the time float, and the perpetually unused benefits, some companies can pocket a pretty profit off these things!