Nobody Remembers Complicated: The Courage to Be Simple

In a world addicted to summaries, the hardest thing to do is say something worth remembering.

What can you say about a twenty-five-year-old girl who died?

That she was beautiful. And brilliant. That she loved Mozart and Bach. And the Beatles. And me.

—Erich Segal, Love Story

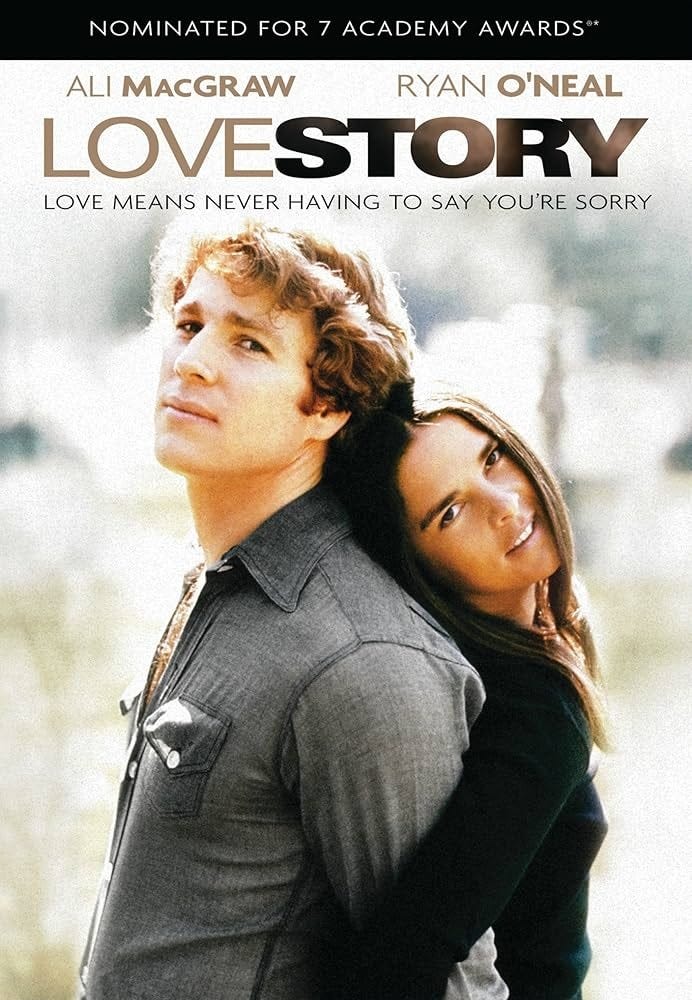

Above: A simple title for a stupendous work of art.

We all know writers who sound brilliant while saying nothing.

But the ones we remember say the most profound things with the most basic prose.

Put simply (pun very much intended): complexity sounds smart, but simplicity gets remembered.

That idea has been looping in my head like a sitcom rerun since devouring Love Story (in one sitting, no less) after finishing Robert Evans’s The Kid Stays in the Picture.

Both are deceptively simple stories—boy meets girl, man meets Hollywood—but beneath their surface is something rarer than brilliance: the courage to be simple, to leave things unsaid.

Evans understood that instinctively. He said movies were like love affairs—keep them moving, keep them feeling, and for God’s sake, don’t explain too much.

Segal did the same.

Love Story beats like a heart: short, steady, unadorned. Its sentences are so smooth that they bleed off the page and the reader can feel the drip of every single drop. That opening line, so stripped of ornament it feels like grief itself, says more than entire novels built of metaphor ever could.

We’ve confused simplicity with stupidity. In our obsession with cleverness, we’ve mistaken clarity for a lack of depth. We pad our writing with jargon and clever turns to sound intelligent, but the best writers use the smallest words to say the hardest things.

Randall Munroe’s Thing Explainer proved this to perfection, describing the International Space Station as the “shared space house,” tectonic plates as the “big flat rocks we live on,” and cells as “the bags of stuff inside you.”

It’s funny, but also profound. After all, the truth doesn’t need adornment to be understood.

We write to be read—but also to be remembered. And remembering requires less, not more.

What’s Lost in Truncation

School taught us to write for readers who are paid to care. Teachers have to finish your essay; editors, investors, and algorithms do not. The tragedy of modern pedagogy is that it rewards verbosity in a world that punishes it.

Out here in the real world, no one has to read you. In fact, most won’t because collectively we have started outsourcing attention itself.

“What are the takeaways?” we ask AI about a 40-minute podcast.

“Summarize the key points,” we demand from YouTube transcripts.

This is a dangerous precedent. Look no further than Click to see what happens when you fast-forward through the banal, only to realize too late that it was the beautiful all along.

Adam Sandler showed us the nightmare of convenience: a life lived entirely on fast-forward, a man who deleted the very moments that made him human.

Something precious gets lost. Not lost in translation, but in truncation.

We no longer live the questions, as Rilke urged us to. We fast-forward to the answers. But “the point is to live everything,” he wrote. “Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.”

Instead, we want the TL;DR version of wisdom—the Ozempic shot for thinking. Results without appetite. Understanding without digestion.

The Ozempification of Everything

As I wrote in The Ozempification of Everything:

[T]he Easy Button is endemic because it is irresistible and quickly coming for all aspects of work and life.

What semaglutide is doing to fat, Generative AI is doing to creativity, inspiration, and meaningful work: gobbling it up entirely.

After all, society now has an Easy Button for white collar work in the form of Generative AI...

The Easy Button attacks society much like cancer does a healthy body: it saps all strength, grows unchecked, gradually takes over, and requires intense, invasive treatment (if it can be cured at all).

This seems like a canary in the coal mine. As the timeless adage goes, “Hard choices, easy life. Easy choices, hard life.”

It leads to a society of pretenders, not practitioners, of LARPers, not leaders (as my friend Regina Gerbeaux so eloquently put it) and strangles at birth the resiliency, creativity, courage, and more that imbue “the crazy ones, the misfits, the rebels, the troublemakers, the round pegs in the square holes” who move society forward.

AI summaries, viral threads, and micro-takes have slimmed our intellectual metabolism. We crave the appearance of thought without its requisite labor. But simplicity isn’t the same as shortness. It’s what remains after everything unnecessary has burned away.

That’s why Love Story endures. It isn’t ornate or ironic or clever or post-modern. It’s just clear. Clear enough to cut straight to the heart.

Its very best lines—“Love means never having to say you’re sorry”—were carved, sanded, and stripped down; after all, it takes hard work to write something that reads easy.

Evans was famous for saying, “There are three sides to every story: yours, mine, and the truth.”

The truth is simple, but never shallow. It’s what’s left when you stop peacocking and start pursuing meaning.

Maybe that’s the real love story—the lifelong affair between simplicity and depth, between saying less and meaning more.

Because it takes courage to be simple, to leave things unsaid.

And in a world addicted to truncation, perhaps the most radical thing we can do is linger.

Per my about page, White Noise is a work of experimentation. I view it as a sort of thinking aloud, a stress testing of my nascent ideas. Through it, I hope to sharpen my opinions against the whetstone of other people’s feedback, commentary, and input.

If you want to discuss any of the ideas or musings mentioned above or have any books, papers, or links that you think would be interesting to share on a future edition of White Noise, please reach out to me by replying to this email or following me on Twitter X.

With sincere gratitude,

Tom

This is very creatively described!

Love this! I wrote a Substack a while ago about having the courage to be "stupid" but this is far better. https://normanwinarsky.substack.com/p/if-you-want-to-be-a-great-founder?utm_source=publication-search