Lorem AIpsum

How to Spot the Nine Telltale Tics of Machine Writing

The poison was never forced — it was offered gently, until you forgot it was poison at all.

—Mark Twain

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.

—Richard P. Feynman

Above: I spy with my little eye Lorem AIpsum.

In the 1964 Supreme Court case Jacobellis v. Ohio, Justice Potter Stewart uttered six famous words that have lived in legal infamy: “I know it when I see it.”

Used to describe his threshold test for obscenity, Justice Stewart wrote:

I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that shorthand description, and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it, and the motion picture involved in this case is not that.

That’s how I feel about AI writing. Hard to define, impossible to pin down, but immediately recognizable. The sentences mimic meaning without ever quite meaning, well…anything.

I’ve spent my whole life attuned to tics. I suffer from Tourette syndrome. My body produces sudden jolts, shrugs, shouts—punctuation marks I never asked for. As a friend once wrote, “[It is] ‘the car alarm’ of neuropsychiatric disorders.”

And yet, I’ve also developed affectionate tics of my own choosing. Nearly every conversation I have with someone meaningful—friend, family, confidant, comrade—ends with five simple words: Love you and God bless.

These two things—Tourette and my so-called tics of love—make me unusually sensitive to the ways patterns shape how we experience language.

And AI has patterns, too.

Shadows Without Substance

In an excellent recent piece, Hollis Robbins describes how AI’s prose creates mirages and shadows that look real but have no substance.

Because she has aphantasia, the inability to form mental images, she sees language differently: not as pictures in the mind but as naked signifiers. This makes her exquisitely sensitive to the way AI writing rings hollow. She writes:

You have a “feeling” that a piece of writing is AI-written. It sounds like word salad, a mashup of textual patterns that gestures toward meaning but isn’t actually anchored in reality.

The reason for all this is how language models work. Briefly, for humans, language unites a signifier (a word, like “tree”) with a signified (an actual or imagined tree). This relationship is arbitrary, though grounded in social convention and human experience. When we use language we are trusting in and building a shared understanding. When someone says or writes “tree” (or arbre, in French) a tree might spring to mind, even if it is wildly different kind of tree than was meant.

Large Language Models (LLMs), however, only operate in the realm of signifiers. There are no signifieds. An LLM generates text through a process called autoregression—it predicts the next word in a sequence based on all the words that came before it. If you give it the phrase, “The cat sat on the…” it analyzes the pattern and predicts “mat” or “chair” as a statistically probable next word. Always keep in mind there is no cat, there is no chair. Autoregressive generation means the AI predicts one word (or token) at a time, using all the previously generated words as context for what should come next. Each new word depends on everything that came before it.

Generally, human writing moves from experience or imagination or observation to linguistic expression. You start with signifieds (concepts, experiences, ideas) and select signifiers (words) to express them. You see or imagine a red chair and write, “That chair is red.”

That hollowness is the calamity of AI: it knows everything but understands nothing, thus resembling a precocious teenager parroting words it half-grasps.

It’s the classic Trump GIF:

Mixed with The Princess Bride:

Like pornography, AI writing is hard to define but easy to recognize. And once you start noticing the patterns, you can’t unsee them.

Core AI Tics

Here’s a non-exhaustive list of the most common “tells” that you’re reading machine-made prose:

The “It’s not X, it’s Y” Antithesis

The most common tell. A fake profundity wrapped in a neat contrast: “We’re not a company, we’re a movement.” “It’s not just a tool, it’s a journey.” Humans use this sparingly; AI uses it compulsively

The Punchline Em-Dash

Every section feels like it’s waiting for a big reveal—until the reveal is obvious or hollow

The Three-Item List

AI loves the rhythm of threes: “clarity, precision, and impact.” It’s a pattern baked deep into training data and reinforced in feedback

Mirrored Metaphors & Faux Gravitas

“We don’t chase trends — trends chase us.” They sound like aphorisms, but they’re cosplay; form without experience

Adverbial Bloat

“Importantly,” “remarkably,” “fundamentally,” “clearly.” Empty intensifiers meant to simulate significance

Mechanical Rhythm

Sentences marching in lockstep, each about the same length. Humans sprawl, stumble, cut themselves off. AI taps its digital foot to a metronome

Hedged Authority

The “at its core,” “in many ways,” “arguably.” A way of sounding wise without taking a stand

Latin Sidebar Syndrome

AI’s compulsive use of e.g. and i.e. often comes with a giveaway glitch: the period-comma doublet (“e.g.,” or “i.e.,”). Almost no human would punctuate this way. Once you’ve seen the “.,” pattern, you can’t unsee it

Closing Tautologies

Ending sections with empty recaps: “This shows why innovation matters.” It looks like a conclusion, but it’s just filler.

Please note that these are not foolproof. After all, AI claims it wrote not only the Declaration of Independence, but also my early, pre-Chat GPT writing.

When the Tics Spread

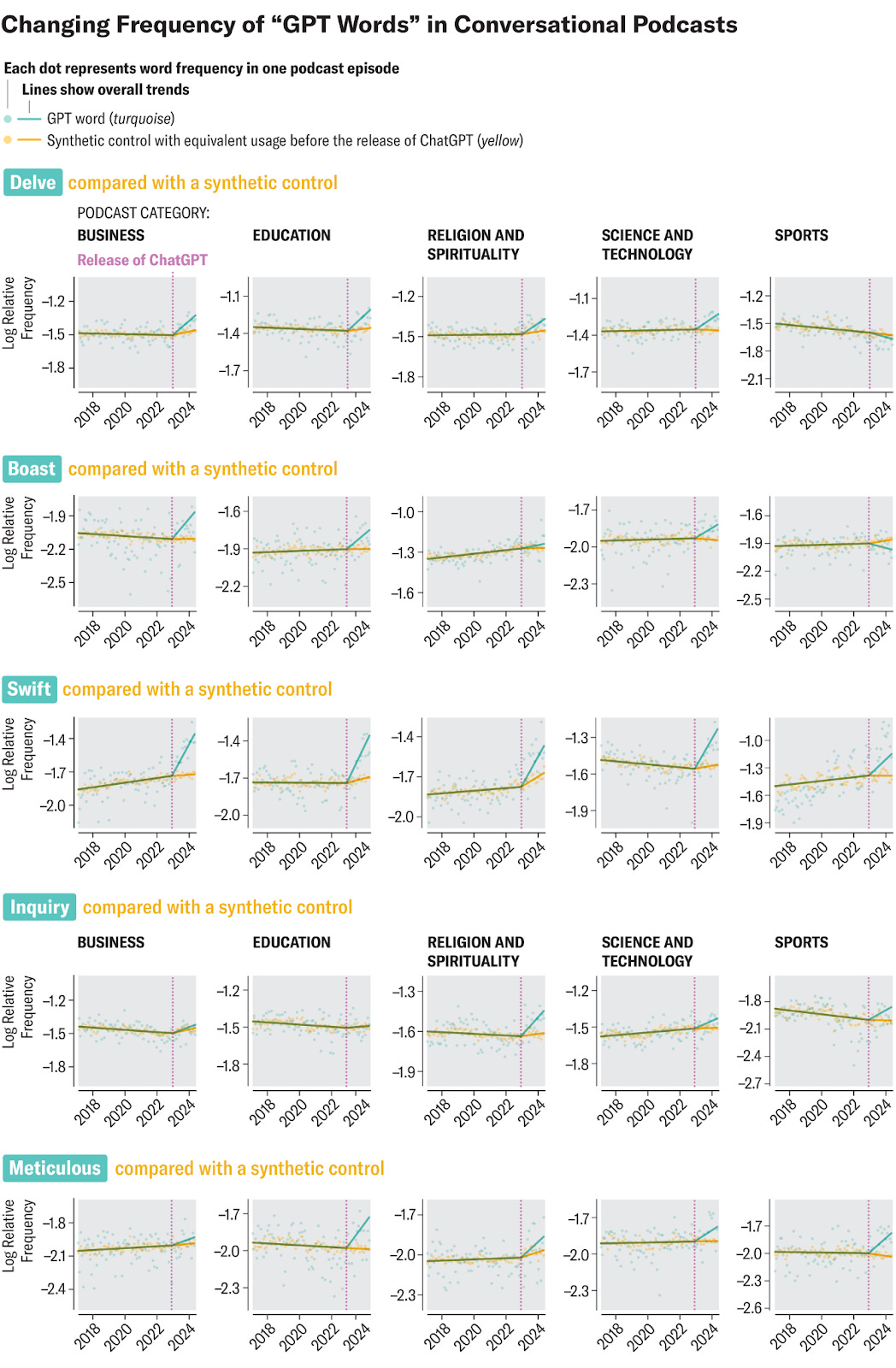

What’s unnerving is that these tics don’t stay confined to machines. They migrate. As the chart above shows, GPT-isms like delve, boast, swift, and meticulous have exploded across podcasts since ChatGPT’s release, far above their natural historical usage.

“The patterns that are stored in AI technology seem to be transmitting back to the human mind,” says study co-author Levin Brinkmann, also at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development. In other words, a sort of cultural feedback loop is forming between humans and AI: we train AI on written text, it parrots a statistically remixed version of that text back to us, and we pick up on its patterns and unconsciously start to mimic them.

Adam Aleksic goes further in a recent write-up:

The reason we’re talking more like Trump and ChatGPT is because our language is being bottlenecked through algorithms and large language models, which do not represent words as they naturally appear: they instead give us flattened simulacra of language. Everything that passes through the algorithm has to generate engagement; everything that passes through LLMs is similarly compressed through biased training data and reinforcement learning. As we interact with these flat versions of language, we circularly begin to incorporate them into our evaluations of how we can speak normally.

The philosophers Deleuze and Guattari would note that these linguistic representations actually perform as mots d’ordre, or “order-words”: utterances that implicitly structure reality and create norms for us to replicate. In the same way that a teacher produces a “grammatically correct” version of English for their students to learn, these new technologies are producing their own version of English, which we’re also replicating.

This is inevitable. ChatGPT and recommendation algorithms are both based on neural networks, a form of artificial intelligence that learns from its inputs to produce new outputs. But those outputs are always going to depend on the inputs, which will always differ from reality, as a map from its territory. So any interaction we have with neural network-based media is going to change our vibes.

Over time, language is sucked of its soul and becomes that much more drab and dull, just like the world around us:

Why It Matters

AI’s tics aren’t just tells; they’re contagious. The algorithm’s speech patterns become ours. Its compulsive em-dashes, its pseudo-profundities, its sterile vocabulary—they are infecting the bloodstream of ordinary conversation.

Good writers are obsessive. They edit, rework, and fuss. The devil is in the details, but so is the soul. AI, by contrast, offers us shadows without weight. Yet as we absorb its habits, we risk mistaking those shadows for the real thing.

The real danger isn’t that AI will write like us—it’s that we’ll start writing like AI.

(Final test: is that paragraph me or ChatGPTom?)

Per my about page, White Noise is a work of experimentation. I view it as a sort of thinking aloud, a stress testing of my nascent ideas. Through it, I hope to sharpen my opinions against the whetstone of other people’s feedback, commentary, and input.

If you want to discuss any of the ideas or musings mentioned above or have any books, papers, or links that you think would be interesting to share on a future edition of White Noise, please reach out to me by replying to this email or following me on Twitter X.

With sincere gratitude,

Tom

Wow this exactly is what I noticed myself, especially when i picked up AI-isms. I was baffled when I started noticing that my own speech was mimicking what I heard on social media or when my writing started sounding robotic because I was reading so much produced by ai. I feel like I am still retraining myself to sound human again

When I was a dean I told my writing faculty in 2022 that their job would utterly change with ChatGPT. They thought they would become more important. I said sure but differently important. Their jobs would go back to being about grammar and structure and prosody, not "how do you feel in words." I mostly believed it when I said it; I wholly believe it now.