Training Until Failure, Thinking Until Fatigue

On the slow atrophy of the mind in the age of effortless creation

I don’t know what I think until I write it down.

―Joan Didion

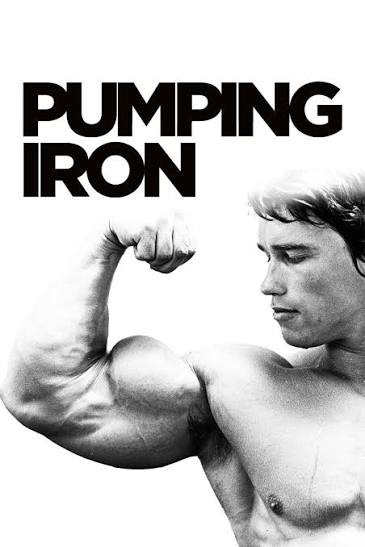

Above: A good movie and a better message.

Watch that line climb.

In less than a decade, the majority of what we read online stopped being written by real, flesh-and-bone humans.

Every paragraph, every headline, every bit of “thought leadership” is now largely assembled by machines that (rather ironically) don’t think, only regurgitate.

We didn’t notice the shift because the sentences still sounded right.

But something else was quietly breaking: us.

The danger of overusing AI for writing is not that it will make your words sound more robotic, but that it will make your mind much less strong.

Just as lifting heavier weights or increasing training intensity triggers new muscle growth, confronting demanding study, complex questions, or emotional struggles builds greater mental capability and adaptability. That’s how neurons grow denser, connections stronger, and the mind sharper. You strain, you tear, you rebuild.

Think of that language you were once fluent in or Euclidean geometry or Avogadro’s number or even derivatives (God forbid!).

The moment you stop using them, they fade.

The same neurons that once lit up with understanding go dark.

If you don’t use it, you lose it and if you refuse to struggle, you atrophy.

The same holds true for writing.

The first 90% is easy: warming up into that sweet flow state when the ideas pour out easily and the sentences don’t hide in the folds of the brain.

But the last 10% is where the work (no, the hell) begins: where you wrestle with phrasing, rhythm, tone, adjective, adverb, sentence, structure, and capital-T Truth, itself. Where every word must earn its place.

That last 10% is where writing becomes thinking.

It’s the mental equivalent of training to failure: pushing past fatigue, through frustration, into focus.

It’s where you stop typing and start understanding.

A recent Nature article put it plainly:

Writing scientific articles is an integral part of the scientific method and common practice to communicate research findings. However, writing is not only about reporting results; it also provides a tool to uncover new thoughts and ideas. Writing compels us to think — not in the chaotic, non-linear way our minds typically wander, but in a structured, intentional manner. By writing it down, we can sort years of research, data and analysis into an actual story, thereby identifying our main message and the influence of our work. This is not merely a philosophical observation; it is backed by scientific evidence. For example, handwriting can lead to widespread brain connectivity and has positive effects on learning and memory.

This is a call to continue recognizing the importance of human-generated scientific writing.

We don’t write to explain what we know.

We write to discover what we think.

But now, we can skip that struggle. Sadly, per the above, the majority now choose to.

AI can draft the paper, write the essay, polish the thought.

It can make you feel like you’ve lifted the weight without ever straining a muscle.

When you remove the friction, you remove the fire (because, per Springsteen, you can’t start a fire without a spark).

You become efficient, but not excellent.

Productive, but not profound.

You get the syntax without the soul.

As I wrote in The Ozempicification of Everything:

Everyone wants to be a founder, no one wants to struggle to make payroll every month.

Everyone wants to be a veteran, no one wants to cradle a friend’s lifeless body in a far-off land.

Everyone wants to be a hero, no one wants to run into a burning building.

Everyone wants to be an author, no one wants to edit a fifty-thousand-word manuscript for the umpteenth time.

Everyone wants to be an athlete, no one wants to run just-one-more wind sprint.

Everyone wants to be a podcaster, no one wants to have a conversation that means something.

The words have meaning because of the actions that back them up.

Without the strain, they’re just syllables—empty forms of effort never felt. Shadows that smell of stolen valor.

The same goes for thought.

When you offload the struggle to machines, you might get clarity faster, but you lose the capacity that clarity comes from. You skip the pressure that turns graphite into diamond.

And without pressure, you stay cold, dull, unremarkable stone.

We used to train until failure.

Now we prompt until comfort.

AI can accelerate, assist, even illuminate, but it cannot strain for you.

It cannot force your neurons to stretch or your mind to break and rebuild itself.

It can make you sound smarter, but it cannot make you smarter.

Writing is the gym of the soul.

Thinking is the weight.

And the struggle, the exquisite, unbearable gauntlet that is the last 10%, is where you grow.

So write until your brain burns.

Think until it hurts.

Train until failure.

Because that’s where the meaning lives: in the strain that no machine can bear on behalf of mind, body, and soul.

Per my about page, White Noise is a work of experimentation. I view it as a sort of thinking aloud, a stress testing of my nascent ideas. Through it, I hope to sharpen my opinions against the whetstone of other people’s feedback, commentary, and input.

If you want to discuss any of the ideas or musings mentioned above or have any books, papers, or links that you think would be interesting to share on a future edition of White Noise, please reach out to me by replying to this email or following me on Twitter X.

With sincere gratitude,

Tom

Yes, I noticed that on my YouTube feed, Tom. I am very interested in World War II videos and documentaries. Up until last year. Most of these videos were narrated by human voice. About a year ago I noticed that many of these content creators switched over to AI narration. This was painfully obvious given the poor pronunciation of many words and phrases. Moreover, many of these AI produced videos, push out, factually incorrect information, the details of which can easily be checked on the Internet. Sadly, artificial intelligence may inundate us with misinformation to the point that we don’t know fact from fiction. Your 90/10 analogy is well taken. Didn’t Edison posit that success was one percent inspiration, and 99% perspiration? Happy writing!

To polish thought with friction as indecision on where to land one’s word stream is, for writers, a runway of pagination with a pausing pen, circling, then landing on the page, or in verbal description of neural energy applied to voicing inner reasoning. When that “writing gym” and “thinking weight” is offloaded to remove the process from mind to machine, the gym empty, the thinking weightless, what proceeds from the person you meet on the street who has no ability to dialogue? How much depth is lost without the firing of neuron sparks (Springsteen, you can’t start a fire without a spark) and what becomes of the luminous fire of MIND when all is consumption without rumination and reflection?