Who Are You Without the Logo?

When the corporate jersey comes off, only one name is left

You think you can win on talent alone? Gentlemen, you don’t have enough talent to win on talent alone.

—Herb Brooks

If you live in the past, you die in the past.

—Mike Ditka

Above: A jersey can give you credibility. It can’t give you identity.

There’s a tremendous scene in Miracle where Herb Brooks finally loses patience with his ragtag bunch of college hockey players.

Throughout the movie, as they prepare for the 1980 Olympics, Brooks’ players keep introducing themselves by citing their college teams—Boston University, Minnesota, North Dakota—like their identity, confidence, and value all live within someone else’s banner.

Finally, fed up, Brooks unloads:

When you pull on that jersey, you represent yourself and your teammates and the name on the front is a hell of a lot more important than the one on the back. Get that through your head!

On the ice, field, or court, that’s true.

In life, it’s backwards.

A 23-year-old who works at McKinsey suddenly has gravitas—not because he knows anything—but because the logo in his email signature confers it.

A fresh graduate at Goldman, Google, a16z, McKinsey, IDEO, Bain (pick your capitalistic cathedral) receives instant credibility simply because the cathedral lets them stand inside its hallowed walls. And the world, erroneously, assumes the institution wouldn’t let an idiot inside.

When you work for a prestigious institution, the world treats you as if you’ve already earned the wisdom, rigor, and experience that come with it.

You walk into a room and the world nods politely—not at you—but at the logo stitched across your chest.

But prestige is a rental; it’s borrowed oxygen that is as flammable as it is unstable.

And you learn that the day your badge deactivates.

The emails get shorter.

The invitations slow.

People start talking to you like you have something to prove.

Because now you do.

Leaving a prestigious institution is a kind of identity detox: you learn, quickly and painfully, which part of your reputation belonged to the name on the front of the jersey and which part belonged to the name on the back.

This explains the universal LinkedIn badge of insecurity: ex-Google. ex-Meta. ex-McKinsey. ex-VC-firm-you’ve-heard-of.

That prefix says everything: You’re not there anymore.

Clinging to “ex-Google” forever is the professional equivalent of telling people: “My ex was Taylor Swift.”

Cool, but she’s not calling you back from Travis Kelce’s arms.

And the world has already moved on.

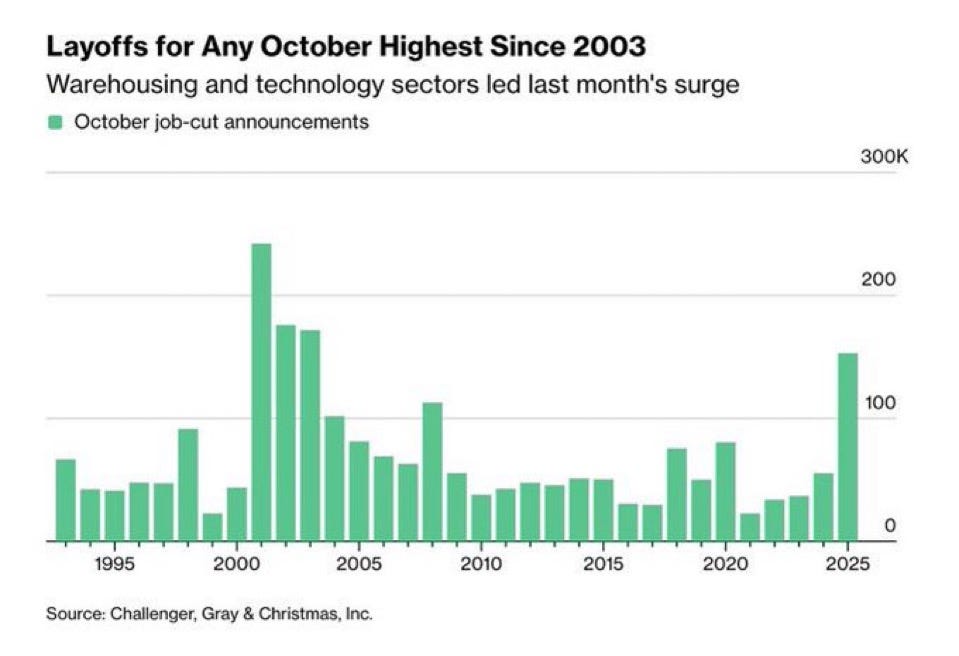

With AI-driven layoffs accelerating—and entire teams evaporating overnight—more people are being forced to confront a truth that was always there: The company was never your family. It was just a team.

And teams cut players, especially when one shows up who is faster, cheaper, tireless, and doesn’t need health insurance or a 401k.

At this moment, the world looks at you—not the badge—and asks the question you’ve avoided: Who are you without the uniform?

That’s the moment people confuse identity with affiliation.

They thought the name on the front was the name on the back.

But the real work—the painful, slow, adult work—is turning borrowed authority into earned reputation.

In response to this, some people panic and spend the rest of their lives trying to recreate institutional safety.

Others do something harder: They make their own name.

David Perell calls it a Personal Monopoly, becoming known for something so distinct, so undeniable, that people recognize your work before they see your signature. He writes:

The ultimate goal…is to build a Personal Monopoly. It’s your unique intersection of skills, interests, and personality traits where you can be known as the best thinker on a topic and open yourself up to the serendipity that makes writing online so special.

The Internet uniquely rewards people with Personal Monopolies because it rewards differentiation. But just as global markets increase the upside of having a Personal Monopoly because every creator can broadcast their ideas to a global audience, they make it hard to create one because of all the competition.

Your Personal Monopoly should reflect your innate interests, not what you think the world wants. There are two reasons why: (1) the Internet creates power law outcomes so if you’re not fascinated by what you’re writing about, you won’t be world-class at it, and (2) due to the immense scale of the Internet, the audience for almost every topic numbers in the thousands. If you’re chasing a trend, you’ve already lost.

That’s the shift: from borrowed, collective credibility to earned, individual reputation.

From “Google alum” to “the guy who built that.”

So here’s the inversion of Herb Brooks’ famous line: If the name on the front mattered more when you started, the name on the back better matter more when you’re done.

Logos fade.

Titles expire.

Companies restructure, automate, and forget.

But a name? One built on craft, consistency, and something no one else can replicate? That lasts.

And, over time, you don’t need the jersey.

You become it.

Per my about page, White Noise is a work of experimentation. I view it as a sort of thinking aloud, a stress testing of my nascent ideas. Through it, I hope to sharpen my opinions against the whetstone of other people’s feedback, commentary, and input.

If you want to discuss any of the ideas or musings mentioned above or have any books, papers, or links that you think would be interesting to share on a future edition of White Noise, please reach out to me by replying to this email or following me on Twitter X.

With sincere gratitude,

Tom

this resonates hard. i went through the withdrawal phase a few years ago after losing my longtime corporate gig with a well known brand. 3 years later, i've managed to take the fledgling side-hustle, nonprofit i had started 2+ decades ago and build it into its own recognized brand. the fact that my prior company was hasbro, the personal monopoly analogy comes with extra oomph ;) -- thanks for the thoughtful writing, i hugely enjoy your work brother.

As someone who recently made a move away from a “biggish” name company to start my own, this really hits home. It’s comforting that some old connections are still connections, because my phone is still ringing. I have the luxury of being selective and giving myself the gift of taking my time back.

But I know it’s not time to rest on any laurels. There is still a daily drive to keep proving it.

Thanks for sharing.