Say Less, Think More

Against "Silence is Violence" and Other Shoddy Slogans

We have two ears and one mouth so we can listen twice as much as we speak. —Diogenes Laertius

God gave us mouths that close and ears that don’t...that should tell us something. —Eugene O’Neill

Above: There would be a lot less monkey business if we all imitated the monkey on the right.

Today a brief note so as to practice what I preach.

The tragedy of today’s communicative commons is that everyone has to weigh in on everything even if they know nothing about it.

The “silence is violence” sloganeering is fatal to the reflection and critical thought necessary to stab at capital-t Truth.

What thrives in this fetid landscape are the many who know a little about a lot. The sage few who know a lot about anything (let alone a little!) are choked and muzzled by invasive species made up of chants, labels, and ad hominem attacks.

This hellscape of tweets, tiktoks, and texts has killed nuance dead; after all, meaningful insight seldom comes from a bumper sticker.

Rather remarkably, back in 2014 novelist Karl Taro Greenfeld offered both diagnosis and prognosis of this paradoxical problem. In “Faking Cultural Literacy” he wrote:

It’s never been so easy to pretend to know so much without actually knowing anything. We pick topical, relevant bits from Facebook, Twitter or emailed news alerts, and then regurgitate them. Instead of watching “Mad Men” or the Super Bowl or the Oscars or a presidential debate, you can simply scroll through someone else’s live-tweeting of it, or read the recaps the next day. Our cultural canon is becoming determined by whatever gets the most clicks…

What we all feel now is the constant pressure to know enough, at all times, lest we be revealed as culturally illiterate. So that we can survive an elevator pitch, a business meeting, a visit to the office kitchenette, a cocktail party, so that we can post, tweet, chat, comment, text as if we have seen, read, watched, listened. What matters to us, awash in petabytes of data, is not necessarily having actually consumed this content firsthand but simply knowing that it exists — and having a position on it, being able to engage in the chatter about it. We come perilously close to performing a pastiche of knowledgeability that is really a new model of know-nothingness…

The information is everywhere, a constant feed in our hands, in our pockets, on our desktops, our cars, even in the cloud. The data stream can’t be shut off. It pours into our lives a rising tide of words, facts, jokes, GIFs, gossip and commentary that threatens to drown us. Perhaps it is this fear of submersion that is behind this insistence that we’ve seen, we’ve read, we know. It’s a none-too-convincing assertion that we are still afloat. So here we are, desperately paddling, making observations about pop culture memes, because to admit that we’ve fallen behind, that we don’t know what anyone is talking about, that we have nothing to say about each passing blip on the screen, is to be dead.

In our society of Bullshit Jobs staffed by professional bullshitters, we have forgotten that bullshit is meant for fertilization, not dialogue. Because of this, not only do we shit where we eat, but also vice versa.

C.S. Lewis’ quote on progress offers the beginnings of a solution:

We all want progress. But progress means getting nearer to the place where you want to be. And if you have taken a wrong turning then to go forward does not get you any nearer. If you are on the wrong road progress means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road and in that case the man who turns back soonest is the most progressive man.

There is nothing progressive about being pig-headed and refusing to admit a mistake.

And I think if you look at the present state of the world it's pretty plain that humanity has been making some big mistake. We're on the wrong road. And if that is so we must go back. Going back is the quickest way on.

Before we march on, powered by pugnacious platitudes, let’s be sure we’re on the right path. That decision ought to be made by our minds, not society’s mobs.

Though speech is abundant, thought is in short supply.

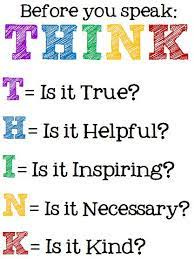

Inspired by Robert Fulghum’s All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten, we would do well to heed this poster:

Per my about page, White Noise is a work of experimentation. I view it as a sort of thinking aloud, a stress testing of my nascent ideas. Through it, I hope to sharpen my opinions against the whetstone of other people’s feedback, commentary, and input.

If you want to discuss any of the ideas or musings mentioned above or have any books, papers, or links that you think would be interesting to share on a future edition of White Noise, please reach out to me by replying to this email or following me on Twitter X.

With sincere gratitude,

Tom