The Great Distraction

How Bread, Circuses, and Push Notifications Explain the Great Stagnation

Distracted from distraction by distraction.

—T.S. Elliot

Everything being a constant carnival, there is no carnival left.

—Victor Hugo

Above: Is technology a leech or a lifeline?

To be human today is to have your attention leased out, minute by minute, to whichever app can scream the loudest.

Screens have become our first glance in the morning and our last look at night. We cradle our phones like talismans and rely upon them like pacifiers, whispering with every tap: please distract me, please numb me.

By doing so, we’re not only spending time, but also squandering ourselves.

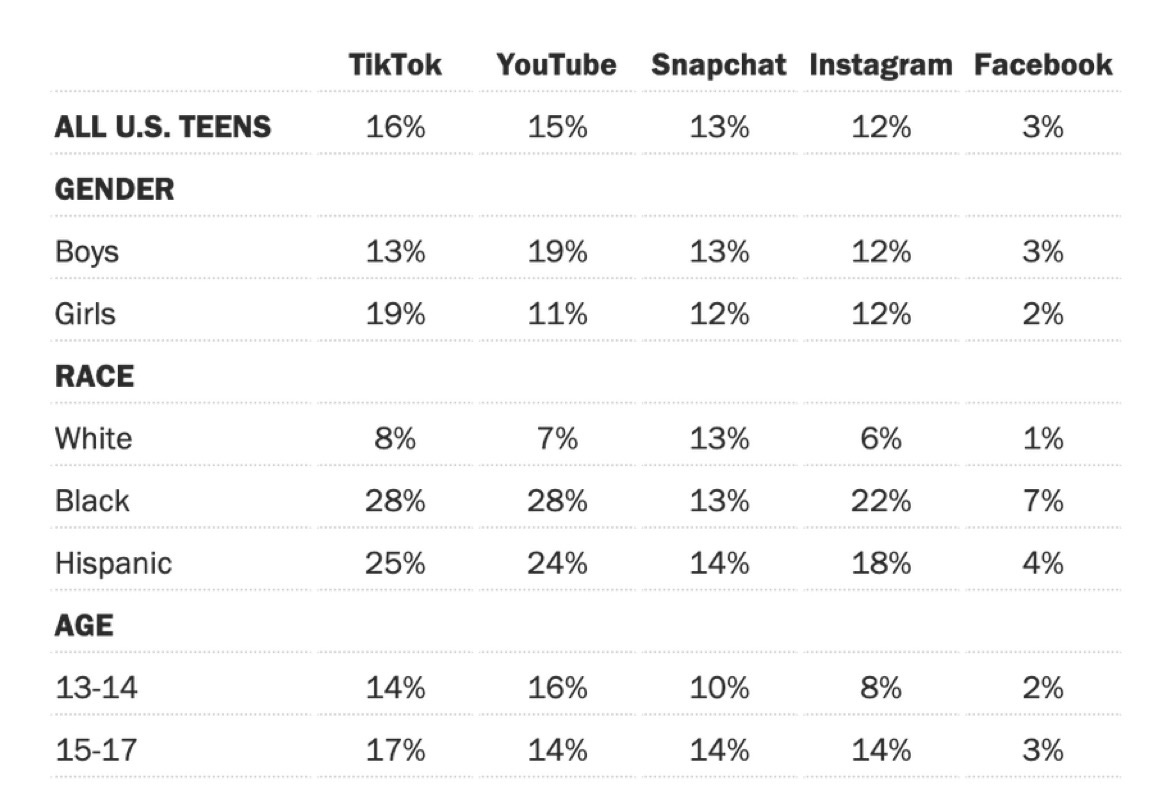

The average human on planet Earth now spends an average of 6 hours and 38 minutes per day staring at a slab of glass, and teens log even more. A 2024 Pew survey clocked constant use (their words, not mine) at:

Translation: every sixth teenager is basically living inside TikTok. We are spending more time with our black mirrors than we are with one another.

Put simply, we are writing checks with our attention that our minds cannot cash.

This hurts not only individuals…

But also society as a whole…

From Burden of Knowledge to Debt of Distraction

There’s an old lament in science called the burden of knowledge: the idea that as fields mature, it gets harder to contribute because the foundation is so vast. You can’t just waltz into physics and make your mark. You have to climb the veritable Everest of what’s already known.

But today we carry something worse: the debt of distraction. We’re too busy refreshing our feeds to even begin. Every new notification is a loan we take out against the possibility of deep focus. Every tab we leave open is a silent tax on our capacity to think.

The dopamine spikes from TikTok or Instagram Reels give us the illusion of being entertained, but the cost is a fractured mind that can’t hold a thought long enough to create something meaningful. We are mentally overdrawn.

This wasn’t always the case. Per Patrick Collison, we used to “quickly [accomplish] ambitious things together.”

His personal site lists out a number of incredible examples:

P-80 Shooting Star. Kelly Johnson and his team designed and delivered the P-80 Shooting Star, the first jet fighter used by the USAF, in 143 days. Source: Skunk Works.

JavaScript. Brendan Eich implemented the first prototype for JavaScript in 10 days, in May 1995. It shipped in beta in September of that year. Source: Brendan Eich's history of the language.

The Empire State Building. Construction was started and finished in 410 days. Source: Empire State Building.

Back when attention was cheap, we shipped miracles. We used to build big things and complete inspiring projects quickly, efficiently, and impressively. These feats were not magic. They were the product of sustained, undiluted attention, the output of a culture that prized focus, urgency, and daring.

Compare that to today. We can’t even schedule a meeting without a Slack thread that devolves into memes and reaction emojis. The best minds of my generation are building algorithms to keep us doomscrolling instead of designing anything that lasts.

Peter Thiel put it bluntly:

When tracked against the admittedly lofty hopes of the 1950s and 1960s, technological progress has fallen short in many domains…Things have been slower and slower for quite some time

What happened?

Collison lists some interesting hypotheses: regulation, complexity, and risk-aversion among others.

Tyler Cowen goes further with his The Great Stagnation: How America Ate All The Low-Hanging Fruit of Modern History, Got Sick, and Will (Eventually) Feel Better:

If one sentence were to sum up the mechanism driving the Great Stagnation, it is this: Recent and current innovation is more geared to private goods than to public goods. That simple observation ties together the three major macroeconomic events of our time: growing income inequality, stagnant median income, and the financial crisis…The American economy has enjoyed … low-hanging fruit since at least the seventeenth century, whether it be free land, … immigrant labor, or powerful new technologies. Yet during the last forty years, that low-hanging fruit started disappearing, and we started pretending it was still there. We have failed to recognize that we are at a technological plateau and the trees are more bare than we would like to think. That’s it. That is what has gone wrong.

As the famous quip goes, “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.”

Yes, regulation, complexity, and risk-aversion all play their part. But the deeper reason is that we have traded our collective attention for entertainment.

Distraction has become humanity’s default operating system.1

Popcorn Brain and The Law of New Toys

We’ve embraced an everything, everywhere, all at once approach:

This is popcorn brain: thoughts that start to pop but never fully form, just half-baked kernels bouncing off the walls of our skulls. We wonder why we feel exhausted and uninspired, but it’s not a mystery. We’ve drowned our minds in a soup of fragmented attention.

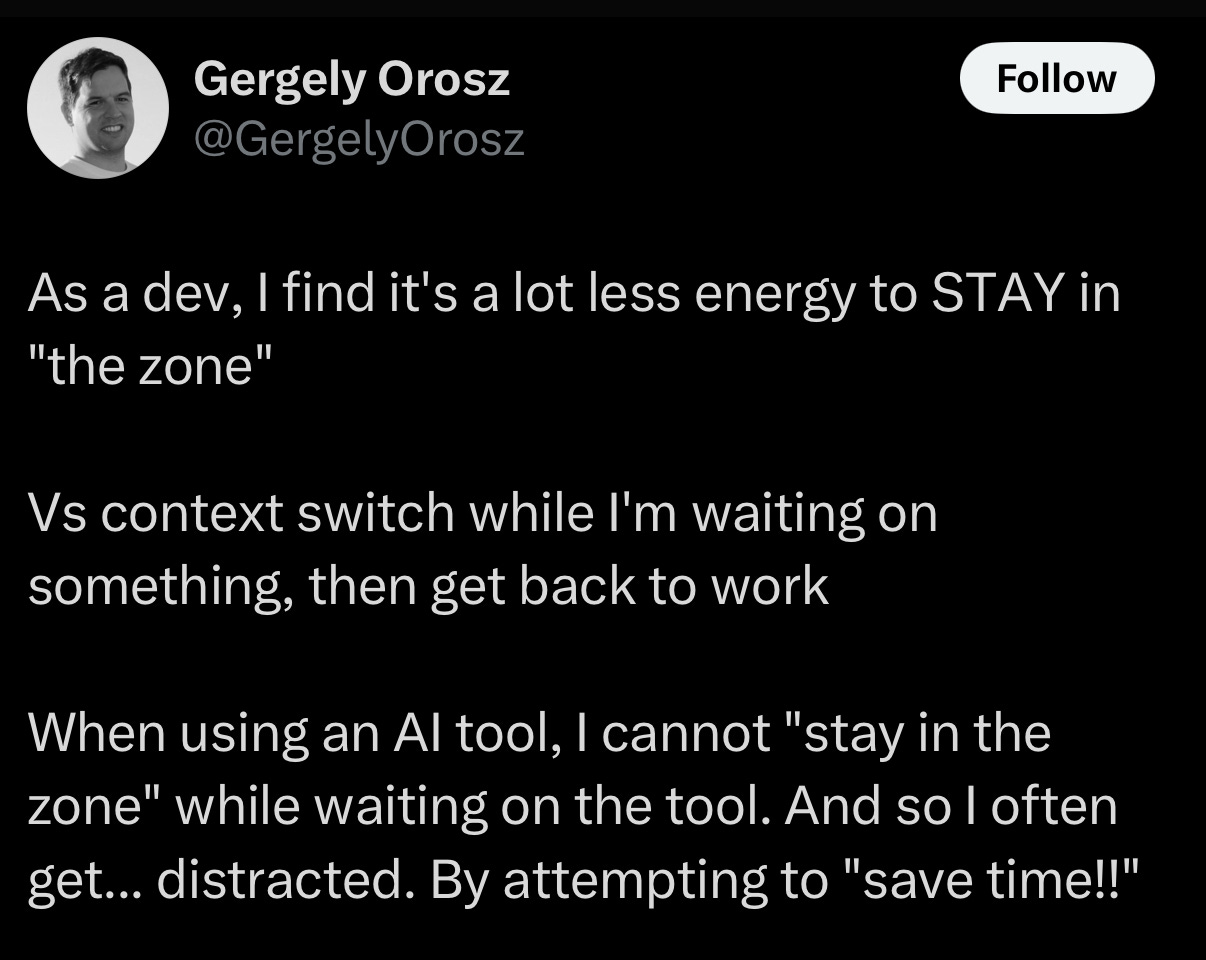

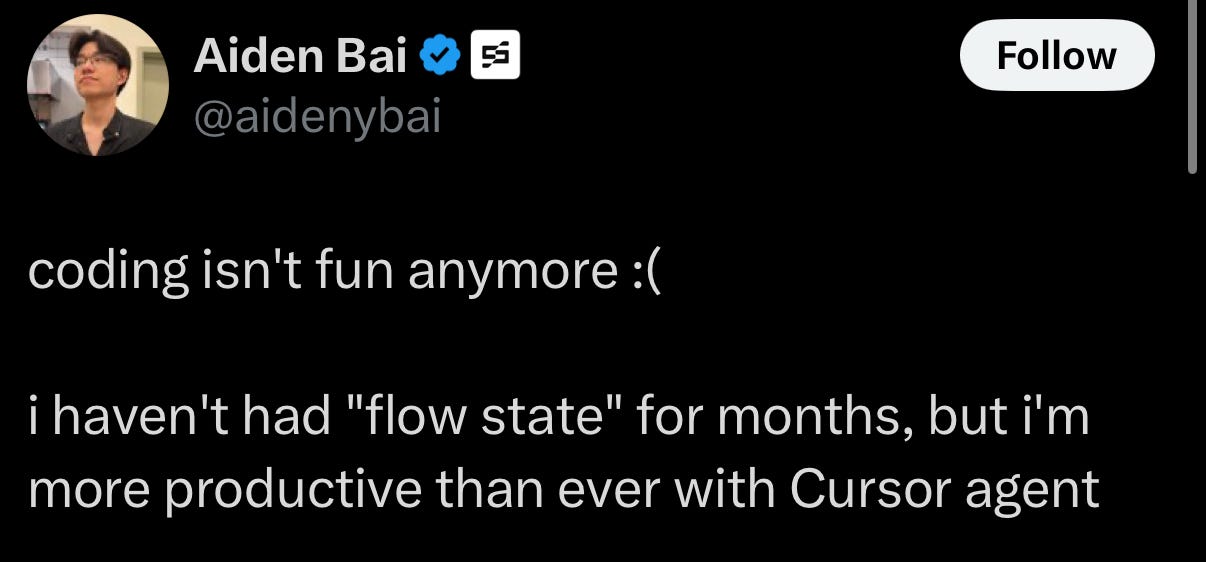

Some recent tweets come to mind:

I’ll offer my own theory: every technological breakthrough is first embraced, then abused.

Cars freed us from distance, then chained us to traffic.

Phones connected us to the world, then made us strangers to the people sitting across from us.

Now social media is erasing the very concept of boredom: a state essential for creative breakthroughs.

Give a human a tool and we’ll use it until it blunts the part of us it once sharpened.

Boredom is a crucible. It’s where Newton saw the apple fall and where Edison brooded over light. Take it away, and you take away the soil where deep thought grows.

Bread and Circuses 2.0

Roman satirist Juvenal wrote:

Already long ago, from when we sold our vote to no man, the People have abdicated our duties; for the People who once upon a time handed out military command, high civil office, legions — everything, now restrains itself and anxiously hopes for just two things: bread and circuses.

What’s old is new again.

Two thousand years later, we have DoorDash and TikTok. Mission accomplished.

Look around: we’re six lanes wide on the information highway, engines revving, GPS screaming, yet the needle is barely moving.

We amuse ourselves to death, as Neil Postman predicted, but the tragedy is that we mistake this endless entertainment for living. We trade the possibility of deep work—of making something real and lasting—for fleeting digital applause. And we’re left hollow, restless, and angry without knowing why.

A Tiny Rebellion

We don’t all need to become monks (though I envy their Wi-Fi-free lives). Instead I suggest we incorporate some more Micro-Monasticism in our lives by carving “monasteries” into our calendars—precious pockets of time reclaimed from the carnival:

Daily 15-Minute Silence: No podcasts, no scrolling, just stillness

One-Window Work: 50 minutes on a single task. No tabs, no notifications

Analog Sabbath: One day a week where your phone is just a phone

A Hard Project: Something worth focusing on. A novel, an open-source tool, a garden. Something that will outlast the dopamine cycle

The same fingers that swipe can still sculpt; the same eyes that glaze can still gaze; the same minds that scroll can still solve.

Close this tab.

Mute the carnival.

Let your brain remember what it feels like to hold a single thought steady.

Pick one stubborn, glorious, daunting thing and give it the focus it deserves.

Quit staring at the spinning wheel; tap refresh, grab a wrench, and build something that loads for good.

Per my about page, White Noise is a work of experimentation. I view it as a sort of thinking aloud, a stress testing of my nascent ideas. Through it, I hope to sharpen my opinions against the whetstone of other people’s feedback, commentary, and input.

If you want to discuss any of the ideas or musings mentioned above or have any books, papers, or links that you think would be interesting to share on a future edition of White Noise, please reach out to me by replying to this email or following me on Twitter X.

With sincere gratitude,

Tom

I’m glad that you’re here, but what are you doing reading this article? If you were honest with yourself, I’m sure you’d see this as a just another form of distraction.

Popcorn brain. Never heard that before and it makes total sense.

Spot on article, completely agree with your perspective.

Technological advances of the past 20 years or so are geared towards locking down a consumer than empowering the human spirit.

Lately, I do my tiny rebellions while commuting or walking to work. No headphones, no book, just fully present with my surroundings. I've found that I have more conversations with strangers, even as simple as helping with directions, because I am leaving myself more "open" to those around me. I quite enjoy it!