This Time is Different

On Venture Capital and the Four Most Dangerous Words in Finance

Losers Average Losers. —Paul Tudor Jones

Above: Stay on the tried and tested course, even if “danger” seems to lurk around the corner.

It’s a tale as old as time.

When you tap the cool blue LinkedIn icon on either iPhone or Android, you are met with barrage of banal, self-congratulatory bromides.

Whether “humbled and honored” or “pleased and privileged,” these announcements on fundraises, promotions, and more pepper one’s feed like basil on pizza. They are as ubiquitous as ads on the internet (and equally as annoying, intrusive, and self-serving).

Many of these posts purport to disrupt this and that.

More, some hail clever new models as disruptive to the very nature of Venture Capital.

Despite this grandiose fervor, venture capital is not changing.

Like a word’s denotation, it is unchangeable — an absolute, a fixed paradigm.

Venture Capital, very simply, funds:

The test of a true, novel hypothesis with…

Enough capital to definitively prove or disprove said hypothesis so as to generate…

Supporting data that makes it clear that the company is worth 5-10x more than it was before.

That’s it.

Yes, it’s that simple.

Like most things, though simple, it is not easy. After all, the map is seldom the territory.

To hammer this home, below are two things Venture Capital is decidedly not:

If you are funding a company to “pour gas on the fire” and replicate/scale already-validated results, that is not venture capital.

If you are funding a company to “run the same, proven playbook” in a different market or geography, that is not venture capital.

This is no value judgment; neither of the above is wrong or bad.

In fact, both serve as a phenomenal way to generate superior returns, especially with copious sums of money. Not to mention, they each serve as indispensable part of properly-functioning capital markets.

It’s just that they are not “Venture Capital.”

This confusion, like most, stems from a lack of linguistic precision. It has its origins in both General Partners and Limited Partners alike misusing the title as a means to justify raising and deploying multiples of capital into venture-capital-financed companies that stayed private—and grew ever more valuable—before ringing any stock exchange’s bell.

Conflation is a son of a gun. The seductive, innocuous logic here points to two canon signs of venture capital investments:

Previous investment by so-called “Venture Capitalists”

Its status as private company

Is this convenient for a venture capitalist’s business model? Yes, very much so.

Does it actually define (or redefine, for that matter) venture capital investing? No, not at all.

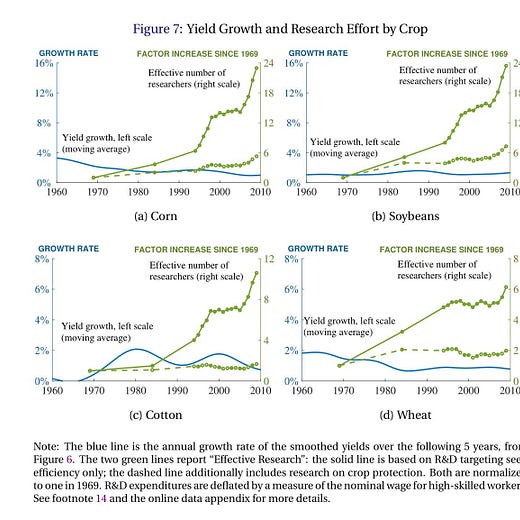

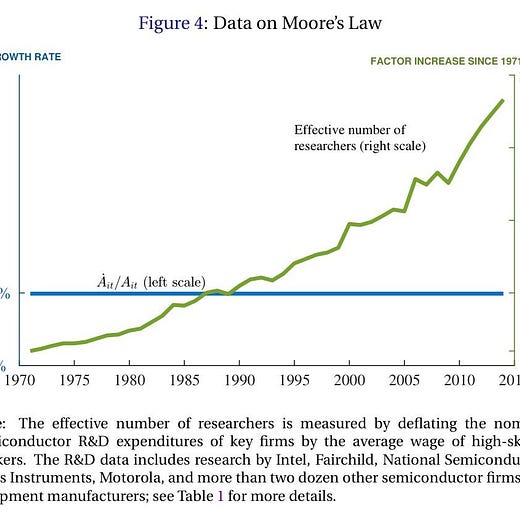

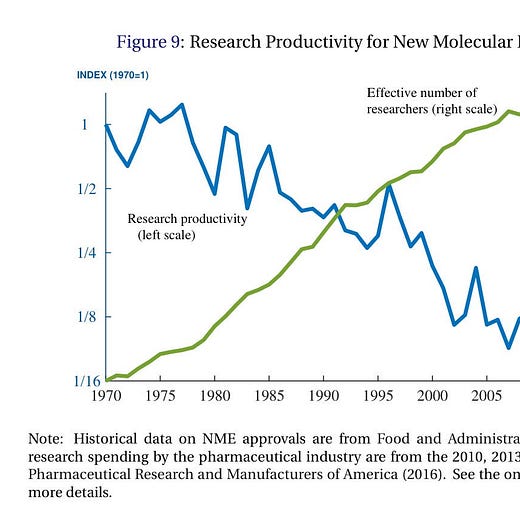

But I digress. I am most concerned with the actual lack of Venture Capital—and subsequent shrinking pool of true venture capitalists—as it relates to proper innovation. A car without wheels cannot roll, neither can societal or technological innovation without risky bets on unproven ideas. After all, the pace of the Red Queen’s race is picking up:

Put simply, if you are raising Venture Capital, do actual Venture Capital. Spades are black and hearts red.

By definition, you will likely succeed a vanishingly-small percentage of the time, but—as the saying goes—that’s a feature, not a bug. The point is to venture—fistfuls of money in hand—at the furthest extremes of capitalism, hoping to stumble upon that rare, proper intersection of technology and commerciality.

By design, most investments will miss the mark.

However, just as a grand slam can change the course of a baseball game, so too does one asymmetric bet on the right team, with the right expertise, in the right market, at the right time.

To ride those winners and to take those losers in stride is to practice venture capital in the purest sense.1

Just as in the below piece, this post was inspired by conversation and correspondence (read as: tutelage) with one of the most adroit thinkers and shrewd investors that I know: Will Quist of Slow Ventures. Look him up, he may well be the most interesting, intelligent, fun allocator you have never heard of.

Per my about page, White Noise is a work of experimentation. I view it as a sort of thinking aloud, a stress testing of my nascent ideas. Through it, I hope to sharpen my opinions against the whetstone of other people’s feedback, commentary, and input.

If you want to discuss any of the ideas or musings mentioned above or have any books, papers, or links that you think would be interesting to share on a future edition of White Noise, please reach out to me by replying to this email or following me on Twitter.

With sincere gratitude,

Tom

Investing is a risky endeavor. Nothing herein constitutes financial advice.

It’s hard to decipher which vcs are legit just via twitter, but it’s a lot easier when you understand the true definition (and check their past investments to match it).

I am not an economist. My point of view might seem by turns Neandertal, Marxist, or anti Tech.

A) You said that we may be suffering from a lack of innovations. I think we are suffering from a deluge of innovations..

Example:

i) The New York Times reported, a few years ago, about a new form of medical malpractice: Doctors' errors occasioned by the onslaught of technical changes, in the equipment they used, that they could not keep up with.

The Times reported that some doctors had given patients drastically inflated and carcinogenic quantities of radiation because the radiologists were overwhelmed and perplexed by incessant software upgrades

ii) The quality of written expression: Writers are so damn busy mastering ever new and superfluous communications technologies that they don't have time for literary excellence. I am sick of the emoticoms, I am sick of noisome flickering images on my computer screen. I want a quiet background graced by, and sparkling with, stuff that shines like Shakespeare.

B) There is too much investment capital:

i) Too much wanton spending and investment bids up the price of goods and services and makes like more unaffordable for common folk

ii) Too much investment capital creates spiraling booms which leads to paralytic crashes, e.g., Before 2007, a superfluity of money in the hands of the big boys led to a real estate boom, which led to a crash, which gave us the great recession.