We Built the Neuralyzer from Men in Black

On a culture engineered to erase the thought we just had.

When a population becomes distracted by trivia, when cultural life is redefined as a perpetual round of entertainments, when serious public conversation becomes a form of baby-talk, when, in short, a people become an audience, and their public business a vaudeville act, then a nation finds itself at risk; culture-death is a clear possibility.

—Neil Postman

Above: A mailbox and a metaphor, all in one.

We used to joke that someday we would invent a technology that would erase our memories like the Neuralyzer from Men in Black.

As it turns out, we needed neither shiny chrome cylinder nor blinding flash of light.

No, all it took was a cancerous sort of abundance: unlimited everything, everywhere, all at once, all the time.

The realization hit me while doing something embarrassingly trivial.

I opened LinkedIn (of all apps!) to send my profile along to a potential client.

Instead, I was greeted by a wall of red.

Five notifications.

Two direct messages.

Three new connection requests.1

A myriad of little red dots designed not to inform but to provoke.

And like a well-trained lab rat, I tapped each and every one with the focused urgency of someone who believed that manipulating pixels meant productivity.

I responded, scrolled, glanced, cleared, reacted, and closed the app.

And only then did it hit me: I had forgotten to do what I had meant to when I opened the app in the first place.

It felt exactly like this:

I find myself doing this increasingly often—I pick up my phones to check the time or weather, see a notification, tap it, and suddenly I’m entirely derailed.

The thought dissolves.

The intention vanishes.

The thread is gone.

My internal monologue goes something like this: Wait…what was I doing again?

Answer:

Nothing.

Everything.

Whatever the machine told me to.

“Distracted from distraction by distraction,” as T.S. Eliot would say.

Colin W.P. Lewis dissected this cultural moment with uncanny precision:

For fifteen years we have been building, at planetary scale, a machinery of disattention: social platforms that auction attention by the millisecond; search engines that outsource memory; feeds that weaponize emotion for engagement.

The result is an economy that grows in inverse proportion to our capacity to think…The youngest generation, those who have never known a world before the machine, are reporting that they can no longer concentrate, remember, or decide.

He continues:

A friend of mine, a novelist, disciplined, once able to lose herself for hours in text, told me recently that she can no longer read a book. Her eyes move, but the mind skitters. “It’s as though my attention has been trained to hover,” she said, “like a cursor that can’t click…

She is not weak. She is collateral damage from being constantly online.

Yet this is larger than individual suffering. A population unable to concentrate, remember, or choose is not merely an unproductive workforce. It is an ungovernable polity. Democracy presumes a citizen capable of following an argument across paragraphs, of remembering yesterday’s promise when voting tomorrow. If cognition fragments, so does self-government. A people who cannot remember are condemned not just to repeat the past, but to be told what the past was, and to believe it.

That’s not exaggeration; the data now exists.

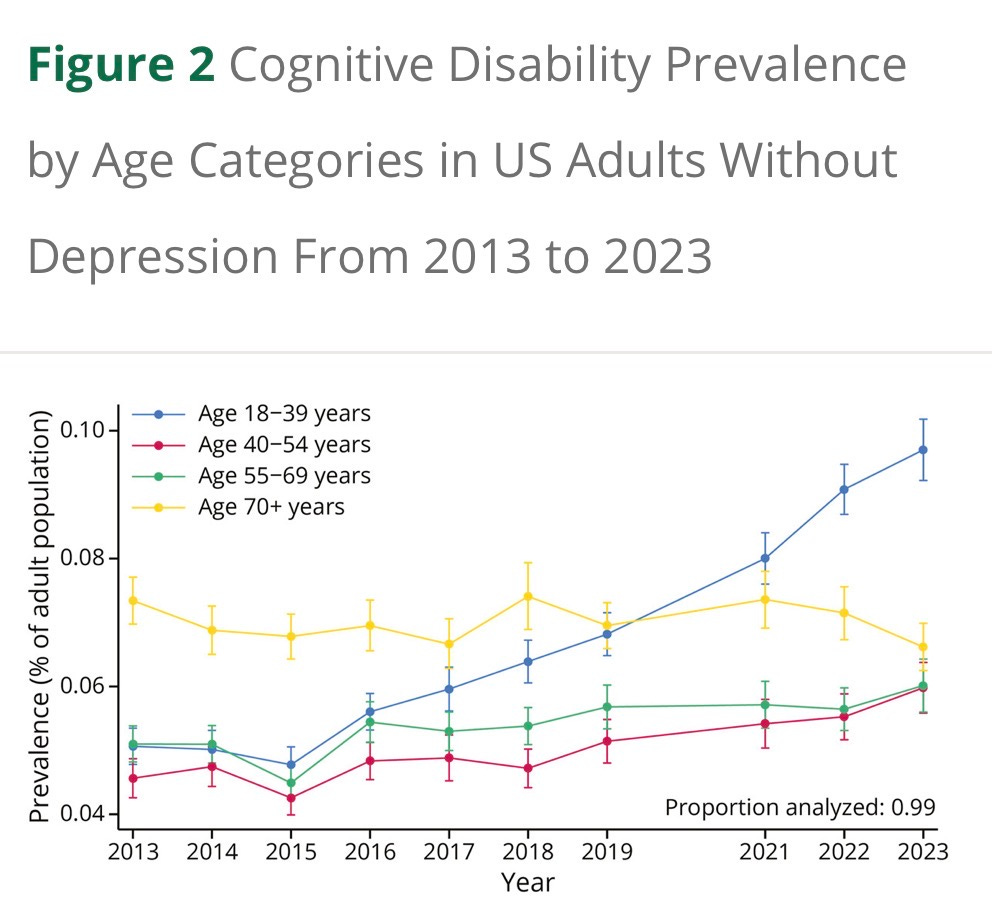

A 2024 Neurology study analyzing over 4.5 million adults between 2013–2023 found:

Cognitive disability in U.S. adults rose from 5.3% to 7.4%

Among ages 18–39, it nearly doubled from 5.1% to 9.7%

The sharpest rise began around 2016 (the year infinite scroll became the default UI of the internet with TikTok’s launch in China)

We used to treat distraction like an inconvenience: the digital equivalent of misplacing your keys or forgetting something at the supermarket.

But this is something pernicious, something bigger and different.

This is forgetting what you were doing while you are doing it.

This is your working memory dissolving mid-thought.

This is a culture where everything is available and, because of this, nothing is absorbed.

Where the loudest thing wins, not the truest.

Where the feed is not only taking our attention, but also our agency and intention.

The tyranny of noise is now so constant, so normalized, that silence feels unsafe—like an interruption rather than restoration.

We mistake the flood for life.

We mistake the notifications for importance.

We mistake the overwhelm for participation.

We don’t realize we’re drowning because the water is warm and everyone else is underwater too.

Somewhere between convenience and abundance, we surrendered something ancient and sacred: the intact human attention span.

And now the Neuralyzer doesn’t flash once.

It flashes constantly.

Every badge.

Every ping.

Every scroll.

Every ring.

And each flash erases one thing: our ability to remember what we meant to do next.

If you made it this far, remember: you didn’t forget on your own.

You were trained to.

And training can be undone.

But if, and only if, we choose signal over noise, put on our sunglasses, and refuse to be blinded by the light.

Per my about page, White Noise is a work of experimentation. I view it as a sort of thinking aloud, a stress testing of my nascent ideas. Through it, I hope to sharpen my opinions against the whetstone of other people’s feedback, commentary, and input.

If you want to discuss any of the ideas or musings mentioned above or have any books, papers, or links that you think would be interesting to share on a future edition of White Noise, please reach out to me by replying to this email or following me on Twitter X.

With sincere gratitude,

Tom

Keep in mind this was LinkedIn! The most grating, least enjoyable redheaded stepchild of social networks.

Yes, LinkedIn used to be the gentleman's club with cognac and cigars ...

And now is more like the disco in a church basement 🤠

And instead of trying to prevent the source of this cognitive decline, we diagnose everyone with ADHD as if the problem is with people's brains and not the society we live in and then we put them on medication. So social media companies, pharmaceutical companies and the rich in general benefit from this but what about the rest of us? And how do we fix things now?