When the First Reader Is a Robot: The Writer’s Dilemma in the Age of AI

Should I write to be found or to make people feel?

This thing we make together. This thing is about hearts and minds, not eyeballs.

—Jeffrey Zeldman

For artists, the great problem to solve is how to get oneself noticed.

—Honoré de Balzac

Above: Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

While pulling together my 2025 White Noise Wrapped, I noticed something that, while understandable and somewhat expected, was still deeply unsettling.

Politics and hot-button issues travel fast (e.g. Blood on the Quad). They get delivered, opened, and read.

Beautiful, evergreen writing that takes more time—the slower, more inward work, like Lifescapes and Maternal Acrobatics—quietly sinks into the digital dustbin of the inbox.

The pattern is obvious. The implication is not.

Both sit upstream of something much larger.

In his annual outlook, investor Tomasz Tunguz predicted that 2026 would be the year the web flips to AI-agent-first design—meaning the primary audience for digital products will no longer be human readers but autonomous AI agents that research, compare, and make purchasing decisions long before a person ever shows up at a website.

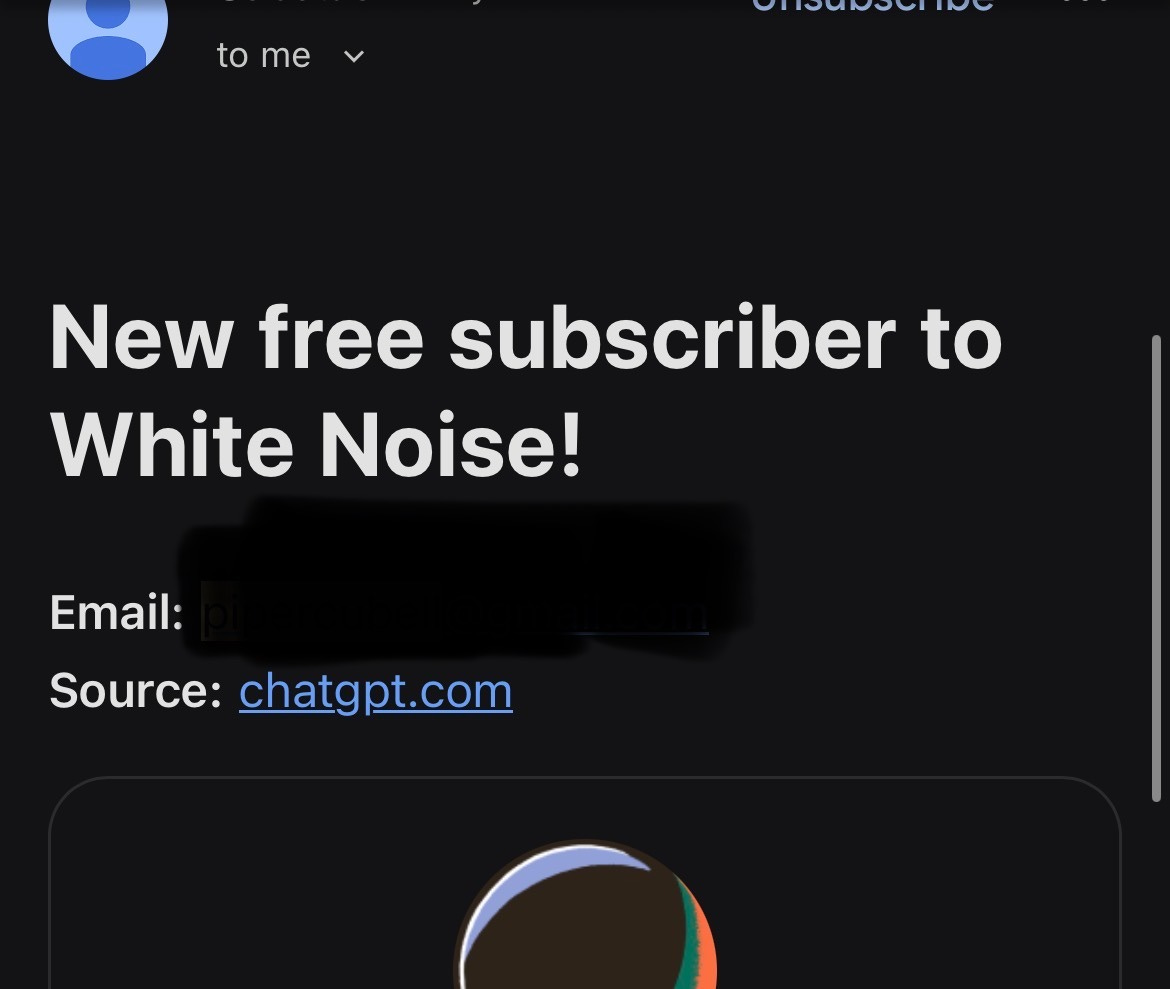

This is already showing up in surprising ways.

Increasingly, when people subscribe to White Noise, the source of the subscription is listed as an AI agent acting on someone’s behalf.

This is just a small preview of the new architecture of discovery.

As Tina He writes in The Race Is On to Redesign Everything for AI Agents, autonomous agents are already performing business-critical roles and evaluating words, widgets, and everything in between without humans ever intervening:

I built an AI agent and set it free to see if it can successfully integrate a tool for me. I’d worked on it and tested it extensively, so I had some idea of what to expect. But still, watching it read through documents for a new tool and then use what it learned to deploy code that actually worked—all on its own—was a heady moment. I thought: We’ve got to start designing everything with agents in mind. Because in addition to millions of humans, your customers will soon be billions of AIs that see the world in a totally different way.

Autonomous agents are already performing a range of business-critical roles. They provide customer support, select vendors, and negotiate deals… I’ve witnessed this firsthand. We built developer tools for humans but found that coding agents were increasingly parsing our documentation—writing code themselves to help with tool integration. Soon, it will be commonplace for agents to work on their own like this, similar to how the one I built did. This demands we reconsider how we build, distribute, and engage with users—be they human or AI.

What He observes is not hand-wavy speculation, but empirical fact: AI systems are acting on information, interpreting documentation, and making decisions. This restructures the very hierarchy of digital attention that first shifted because of algorithms.

In short, the front door of the web is now being designed for robots that crave structure, readability, and predictability while the side door still exists for humans moved by storytelling, nuance, ambiguity, voice.

But that dual architecture creates a tension writers must confront: Do we optimize for discovery by agents, or for resonance with humans?

This mirrors what decision theorists call the exploration–exploitation dilemma.

Exploration favors novelty, risk, and discovery—venturing into unknown territory in search of something better.

Exploitation favors reliability—doubling down on what already works.

In an agent-first web, writing optimized for discovery is a form of exploitation: structured, predictable, legible to machines.

Writing that moves humans is exploration: high-variance, irreducible, resistant to compression

The system rewards exploitation, but meaning is born in exploration.

And writers now have to choose, sentence by sentence, which game they’re playing.

The writing that agents find may not be the writing that moves us.

And the writing that moves us often resists reduction into the clean, machine-friendly patterns that agentic systems prioritize.

This is where the tension turns pathological.

Agent-friendly writing demands clarity, predictability, sameness.

Human-moving writing depends on ambiguity, texture, voice, risk.

Agents want answers.

People want resonance.

Agents reward the reducible.

People remember the irreducible.

Agents want structure.

People want soul.

The pressure is only intensifying.

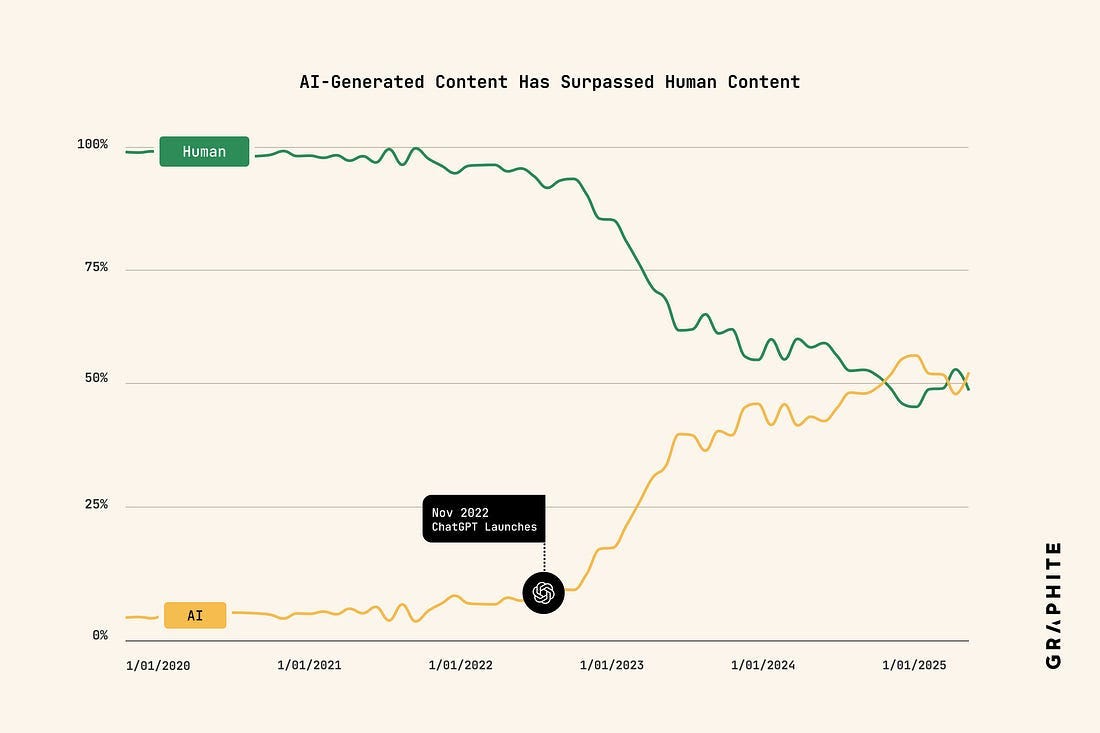

Digital marketing firm Graphite recently concluded that more articles are now created by AI than by humans.

Generative AI destroys the scarcity that once gave average professionals a career; this is first a tragedy for the worker and a miracle for the consumer, and eventually a miracle only for those who profit from selling low-quality slop.

It stands to reason, then—just as an Irishman prefers Guinness, or a Frenchman wine—that machines will prefer their own mechanically generated fare. When algorithms become the dominant readers, they will naturally reward what looks most like themselves.

So writers face an unspoken choice: Write to be surfaced or write to be felt.

Most “content” chooses the former. It must. It is designed to survive ingestion, not contemplation. It is optimized to be summarized, not savored. It passes cleanly through machines and leaves no residue in the human nervous system.

But the writing that actually enlarges us—the kind that animates, disturbs, lingers—resists reduction. It doesn’t slot neatly into comparison tables or bullet-point verdicts. It cannot be safely compressed without losing the very thing that made it vivacious.1

So it disappears because it refuses to behave, relegated to the back of the bookshop by proprietors with neither skin nor soul.

In short, we are building a web where legibility to machines precedes meaning for humans.

Where discovery is automated and depth is accidental.

Where the most human sentences are the least indexable.

The danger is that writers will quietly stop trying to move anyone—mistaking visibility for vitality, reach for resonance, ingestion for impact.

The dilemma is real. But so is the wager.

Because every agent-first world eventually starves for something it cannot summarize.

And when it does, the side doors matter more than the front ones ever did.

If the front door of the web now belongs to agents, then consider White Noise a side door. A quieter, ramshackle sort of entrance. A place for words that resist compression and sentences that won’t sit still.

This has—and will likely continue to—limit how often it’s found or read or shared. But it preserves the reason it’s written at all.

Per my about page, White Noise is a work of experimentation. I view it as a sort of thinking aloud, a stress testing of my nascent ideas. Through it, I hope to sharpen my opinions against the whetstone of other people’s feedback, commentary, and input.

If you want to discuss any of the ideas or musings mentioned above or have any books, papers, or links that you think would be interesting to share on a future edition of White Noise, please reach out to me by replying to this email or following me on X.

With sincere gratitude,

Tom

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.” is much more compelling than any simplified Sparknotes synopsis.

Dang, bro.

I find your writings generally thought-provoking and very insightful and I enjoy all your posts.

I also found you without the use of a chatbot…and further, I can’t personally imagine ever wanting to delegate the experiences of discovery of new writers and things to read - or other media I generally consume, such as music or movies, etc - to any chatbot, certainly at current levels of reading proficiency.

I say then, keep trying to write the beautiful sentences humans will find compelling - any AI worth anything will be able to soon optimize to understand these nuances more and more. If AI doesn’t do that, what’s it good for anyway? In that case, everything is completely meaningless anyway, so just keep writing for humans and we will continue to discover the likes of you by traditional methods until we’re not allowed to anymore!