Why Does Everyone Love Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations?

Marcus Aurelius Inadvertently Cracked the Influencer Code

The multitude of books is a distraction.

—Seneca the Younger

We have more choice than ever before, but no matter what we choose, we have lost the ability to really pay attention to it.

—Yuval Noah Harari

Above: Marcus Aurelius as a millennial.

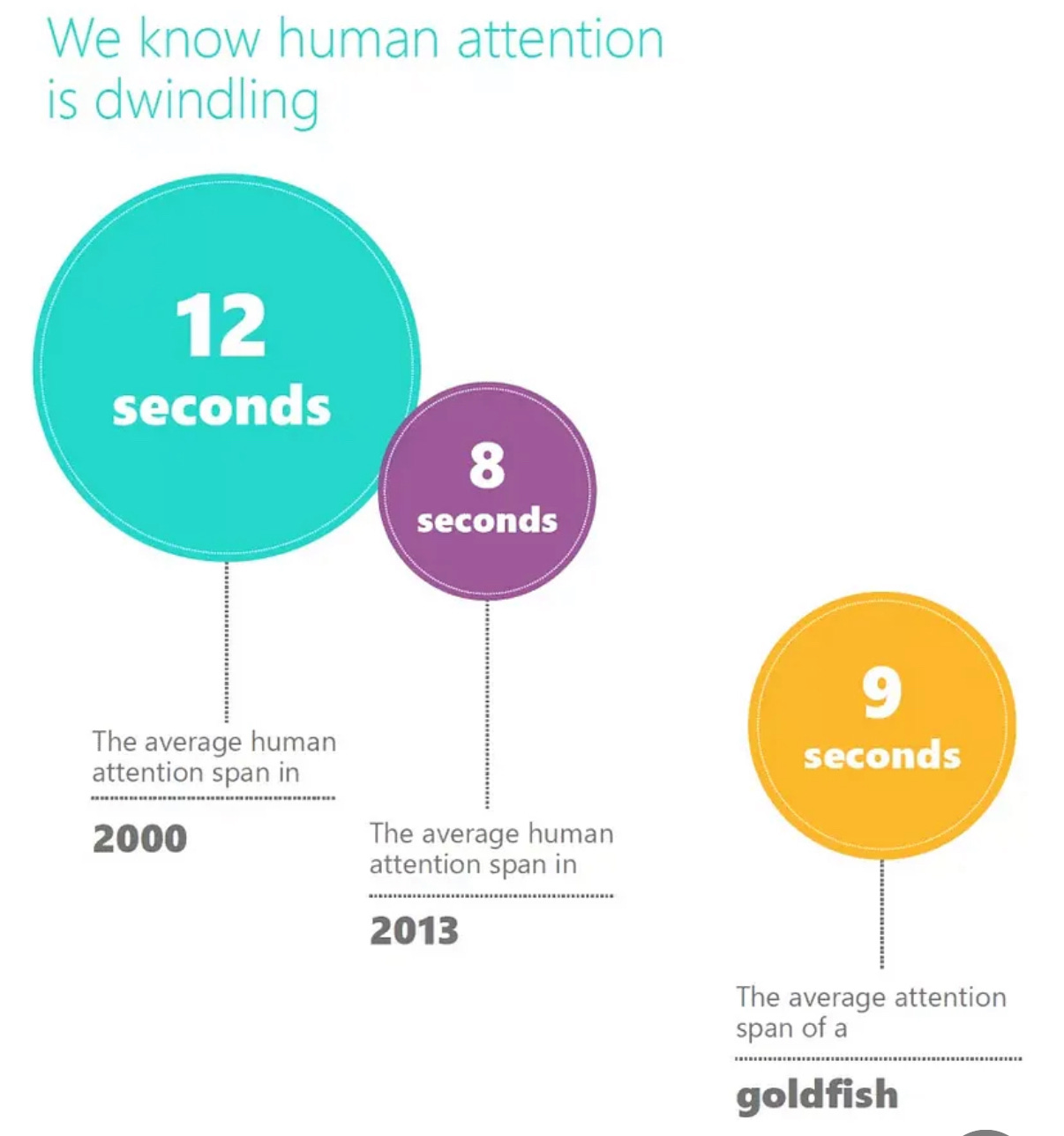

It’s a truth universally acknowledged (and personally felt every time my phone buzzes) that being online fries focus.

By the time you finish this sentence, a few more milliseconds of your attention will have vaporized.

Both memes and metrics support this.

In our fast-paced digital age, attention has become a prized commodity.

With instant gratification at everyone’s fingertips, capturing it has become even harder.

The repercussions of this shift are vividly evident in our contemporary media consumption habits, where short-form video content has quietly risen to dominance (Hell, even LinkedIn is pushing video in some devilish effort to become a sort of white-collar TikTok).

Unconvinced? Look no further than the Radio Star or prolific writer and venture capitalist Tom Tunguz, who analyzed his blog in a fascinating piece entitled This Message Will Self-Destruct in 33 Seconds:

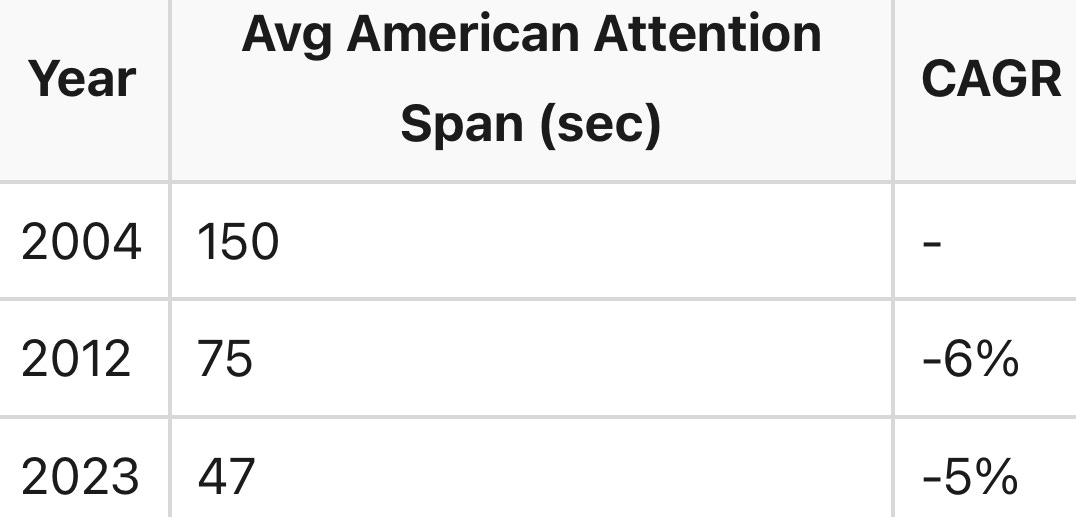

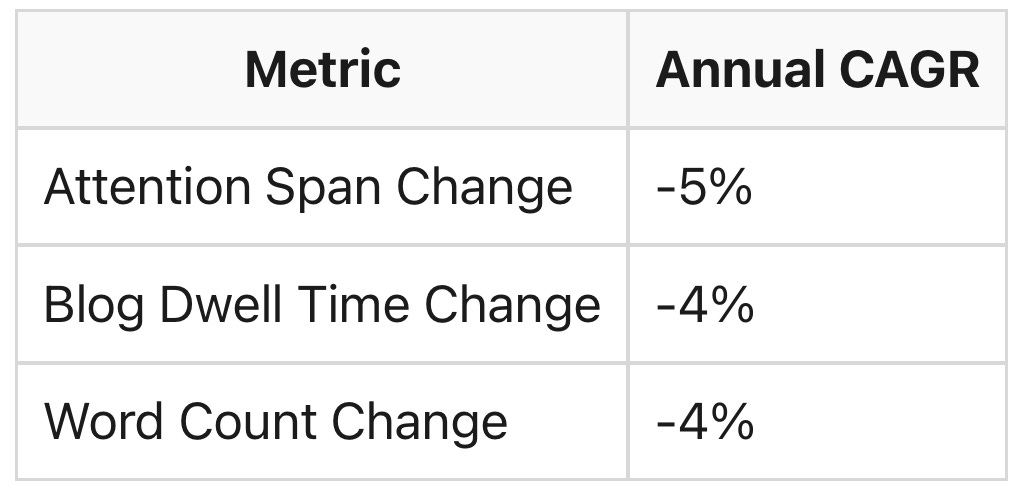

The average American attention span has fallen from 150 seconds in 2004 to 75 seconds in 2012 to 47 seconds in 2023 - a 5-6% rate of decline.

In 2013, the average reader dwelled on this site for 47 seconds.

Today, it’s 33 seconds, a 3.6% decline - which is a bit better! But probably within the realm of statistical noise.

Over the past decade, the average word count per post on this site has fallen 40% from approximately 560 at the peak to approximately 350 today.

So the deflation is consistent. We could argue the posts themselves are shorter, which reduces dwell time - but it’s the other way around.

Content on the internet has compressed: YouTube shorts & tweets come to mind. They provide a faster time to value/dopamine. Authors, rewarded for shorter content, mirror the rest of the web.

Walter Kirn’s one-sentence summary of contemporary media is stuck in my head: “This is a world-concealing layer of diversionary and illogical and internally inconsistent noise, under which the world exists somewhere.”

The eternal weight of ephemerality and the heaviness of bits and bytes has fascinated me for quite some time. A recent piece of mine attempts to capture this paradoxical concept:

So much content (yuck), so little time summed up a recent conversation with my friend R.W. Richey. Fresh off his first read of Meditations, we discussed the book‘s impressive staying power and surging popularity.

Our hunch: its pure structural advantage.

That is, not so much what it says (which, to be clear, is exceptional), but how it says it.

Some cursory research lends credence in this idea:

Total word count: ~52,000 words in a standard Collins Classics text (about half a typical modern novel).

Books (“chapters”): 12 self-contained notebooks.

Average words per book: roughly 4,000–6,000 (around 15–20 minutes of reading each).

Discrete entries: about 488 individual aphoristic paragraphs, averaging ~100 words apiece.

Typical sentence length/readability: ~20 words per sentence; reads at roughly an 11th-grade level on Flesch-Kincaid.

Shortest entry: Book 11.18—just four Greek words (“σκόπει ἑαυτόν,” “Look within”).

Full-book reading time: ≈3.5 hours at 250 wpm—comparable to a long podcast binge or several short-form-video sessions.

Lining those stats up against modern dopamine loops:

Short-form symmetry: The average TikTok video in 2024 clocks in at 42.7s while users spend ~58 min/day scrolling. Reading a single Meditations notebook (~18 min) delivers a comparable “completion buzz” to watching a handful of reels, but with deeper narrative payoff.

Chunked delivery: Scroll culture rewards bite-sized packets. Aurelius pre-figured the format: modular thoughts you can dip in and out of, no storyline lost. Cognitive-psych studies show that task-switching costs drop when content comes in discrete micro-segments, exactly what Meditations provides

Variable reward schedule: Just as an algorithm occasionally serves a viral clip, Meditations sprinkles pithy one-liners (“Waste no more time arguing what a good man should be. Be one.”) among longer reflections. Dopamine spikes on surprise novelty, not just length; the unpredictable entry sizes exploit the same mechanism.

The Paideia Institute agrees, labeling this “Social Media Stoicism” (emphasis mine):

[T]his reflects the overwhelming influence of social media in the contemporary world where billions of users publicly share so much of their lives, opening themselves up to negative comments, arguments, criticism, and, most commonly, comparing themselves with others in a way that causes them to feel negatively about themselves and their lives. Rather than being concerned with Marcus Aurelius’ idea of a rational mind or cultivating a virtuous life, social media audiences are concerned with navigating the chaos of the modern world, exacerbated by constant media, documentation, and unrealistic expectations. It is for these reasons that the concept of acceptance, focusing on things within one’s immediate control, and living in the moment are so attractive…

The prevalence of Social Media Stoicism, then, illustrates the digitization of self-help with a focus on the idea of the individual and the problems they face–something particularly emblematic of the modern age. The self-serve accessibility of Stoicism and texts like the Meditations may be less than scholarly. But this is the very nature of popular philosophy, which often changes or emerges alongside historical and generational development…

Stoicism's digital renaissance reflects contemporary frameworks of content consumption and challenges around fast-moving information, the prevalence of public attention, and the internal chaos it can cause.

And yet, the irony is palpable; as Marcus Aurelius himself wrote in Meditations, “The speed with which all of them vanish—the objects in the world, and the memory of them in time. And the real nature of the things our senses experience, especially those that entice us with pleasure or frighten us with pain or are loudly trumpeted by pride. To understand those things — how stupid, contemptible, grimy, decaying, and dead they are — that’s what our intellectual powers are for.”

Virgil whispered the same centuries earlier: fugit irreparabile tempus—time escapes, irretrievably.

So where does this leave our poor, poor attention spans?

Though correlation is not causality, I think this points back to the importance of the four Cs when communicating:

Clear: Avoid ambiguity, be direct, and use simple words/sentences.

Concise: Be brief.

Cogent: Ensure your writing follows a logical, relevant sequence. Each point should naturally lead to the next, building a cohesive argument backed up by data, examples, and/or testimonials.

Comprehensive: Be thorough by covering your bases and anticipating questions.

Where this leads us no one can be sure, but the proliferation of what Harrison Moore calls the thread boi writing system might, terrifyingly, be a logical next step:

Soon enough, it may turn out that none other than Kevin Malone was way ahead of his time.

May your swipes be wise and your attention apt.

Vale!

Per my about page, White Noise is a work of experimentation. I view it as a sort of thinking aloud, a stress testing of my nascent ideas. Through it, I hope to sharpen my opinions against the whetstone of other people’s feedback, commentary, and input.

If you want to discuss any of the ideas or musings mentioned above or have any books, papers, or links that you think would be interesting to share on a future edition of White Noise, please reach out to me by replying to this email or following me on Twitter X.

With sincere gratitude,

Tom

Really interesting analysis Tom. Haven't got to read Meditations, but did sometimes wondered why so many people who I would consider non-readers, certainly non-philosophy readers, have read it and got through it. Learnings seem bite sized and easily shared as well.

OMG! I hated all the images in this piece. They are so distracting. I get that was the point, however, it certainly interrupted the flow of your wonderfully insightful prose.