On Awe and Annihilation in the Age of AI

Our Three Futures

To have agency is to be the subject of a sentence, rather than its direct object. It is the tendency to act, rather than wait to be acted upon.

—Devon Eriksen

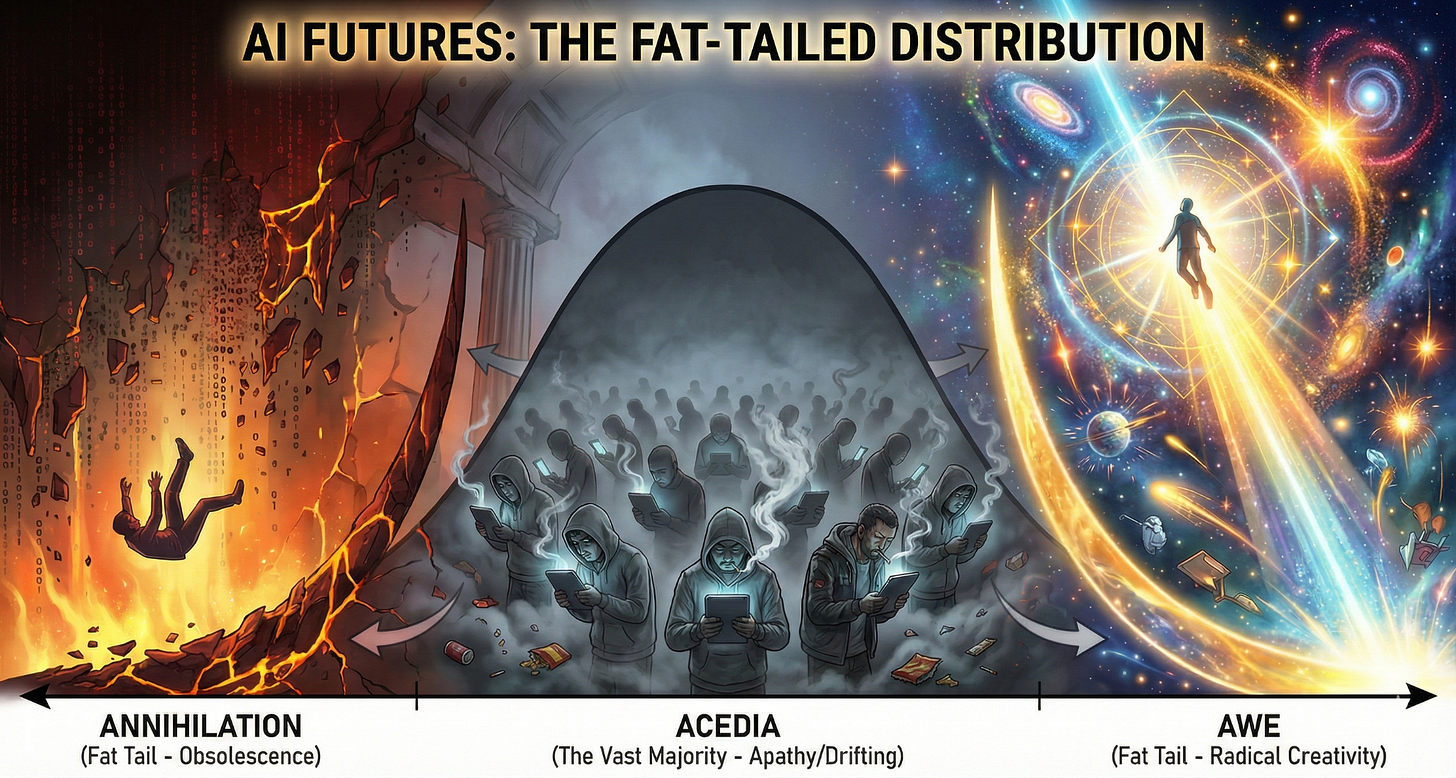

Above: Which way, dear reader?

The people at the jagged edge—the misty frontier where artificial clouds mushroom before they blot out the sun—are now saying the quiet part out loud.

Here’s Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, in his recent essay “The Adolescence of Technology”—a long read, but an indispensable one if you want to understand the potholes and pitfalls that mar humanity’s precarious journey toward AGI:

We are now at the point where AI models are beginning to make progress in solving unsolved mathematical problems, and are good enough at coding that some of the strongest engineers I’ve ever met are now handing over almost all their coding to AI. Three years ago, AI struggled with elementary school arithmetic problems and was barely capable of writing a single line of code. Similar rates of improvement are occurring across biological science, finance, physics, and a variety of agentic tasks. If the exponential continues—which is not certain, but now has a decade-long track record supporting it—then it cannot possibly be more than a few years before AI is better than humans at essentially everything.

Better than humans. At essentially everything.

That line sits there like a stone in the stomach and forces the next question:

Where does that leave us?

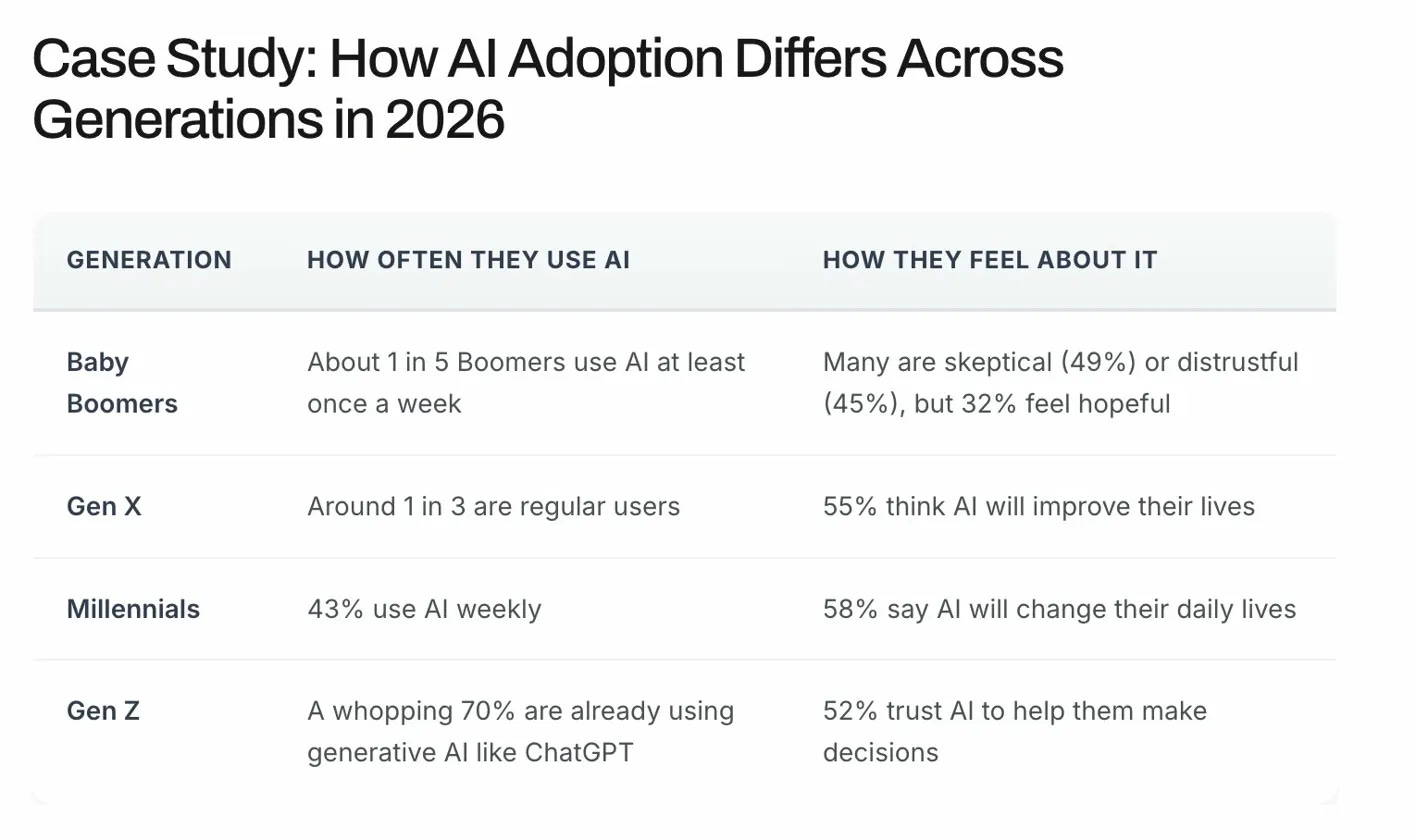

As with any substance, the dose makes the poison. And right now, most of the working world is mainlining AI straight into the aorta:

Let’s take the young bucks: Gen Z. Seventy percent already use generative AI weekly. Over half trust this alien technology to help them make real-life decisions.1

This is dependency formation in real time. First we use a tool. Then we lean on it. Then we can’t imagine doing without it.

Worse still, it points toward a future most people haven’t bothered to imagine.

I see three paths.

Annihilation — Obsolescence and ruin.

You’ve seen this future. It’s the humans in WALL-E—floating on recliners, atrophied and infantilized, having outsourced not just their labor but their will. Not dead. But not really alive either. No more than furniture with faces.

A future where comfort is cheap and agency is optional tends to end with agency disappearing.

Acedia — Grey, apathetic drifting.

If you want to see this future rendered in fiction, read Michel Houellebecq. Pick up Submission or Serotonin. His protagonists don’t rage against the dying of the light. They simply... stop caring. They smoke. They scroll. They exist. They wait to be acted upon.

AI makes that life easier to sustain. It smooths friction. It fills the silence. It turns thinking into a service you subscribe to.

Awe — Radical creativity and breakthrough.

Think Tony Stark in his workshop. Not competing with the machine but dancing with it—using it as a lever to move atoms and bits and bytes that couldn’t be moved before. The human who becomes more human through technology, not less.

Awe is not “inspiration.” It’s directed power in the hands of someone who remains awake.

The vast majority will settle into the comfortable, grey, miasmatic middle of Acedia.

But watch the fat tails. The statistical extremes—total wonder or total collapse—are much thicker probabilities than we like to admit.

So how do you choose Awe?

You don’t. Not directly, at least.

Like happiness, it is a byproduct derived from purpose, function, or conflict.

You can’t grit your teeth and willpower your way there. That’s just Boxer from Animal Farm—the cart-horse whose answer to everything was “I will work harder!”

But that response becomes meaningless—suicidal, even—in a world where AI does everything better, faster, cheaper.

The real fork is simpler and harder: whether we can still choose at all.

Because modern life trains reactivity. Feeds, notifications, incentives, nudges. A day made of inputs. A mind trained to respond. We lose the muscle slowly, then all at once.2

There is a way through. It was mapped decades ago by Josef Pieper in a book that should be required reading for anyone trying to stay human in the age of machines: Leisure: The Basis of Culture.

Leisure is neither laziness nor consumption. Pieper is precise:

Leisure, it must be remembered, is not a Sunday afternoon idyll, but the preserve of freedom, of education and culture, and of that undiminished humanity which views the world as a whole.

This is the bridge to Awe.

But it can’t be instrumentalized. You can’t optimize your way there. Pieper again:

Leisure is only possible when we are at one with ourselves. We tend to overwork as a means of self-escape, as a way of trying to justify our existence...

Leisure cannot be achieved at all when it is sought as a means to an end, even though that end be ‘the salvation of Western civilization’. Celebration of God in worship cannot be done unless it is done for its own sake. That most sublime form of affirmation of the world as a whole is the fountainhead of leisure.

The fountainhead.

Not an escape from the world. The only way to actually live and be present in it.

This is what we've forgotten. We've confused producing with living. We've traded the Three F's—Faith, Family, and Friends—for the fluorescent hum of adult daycare and choked stiffness of white collars. We've become so fixated on output that we've forgotten how miraculous our existence is, how marvelous our bodies are, how much of life happens in the spaces between tasks.

Our way out lies in remembering these small, quiet miracles.

The machines will take everything we do. Let them come.

They cannot automate stillness.

They cannot optimize wonder.

They cannot code the moment your chest fills for no reason at all—looking at your child, or the sea, or the light through a window you’ve passed a thousand times.

That capacity—to be struck, to be still, to worship something beyond yourself—is not theirs to take.

Unless we hand it over.

Per my about page, White Noise is a work of experimentation. I view it as a sort of thinking aloud, a stress testing of my nascent ideas. Through it, I hope to sharpen my opinions against the whetstone of other people’s feedback, commentary, and input.

If you want to discuss any of the ideas or musings mentioned above or have any books, papers, or links that you think would be interesting to share in a future edition of White Noise, please reach out to me by replying to this email or following me on X.

With sincere gratitude,

Tom

Given how fast things are moving, this is likely an underestimation. This data comes from September of 2025.

Pieper called this too: “[T]he greatest menace to our capacity for contemplation is the incessant fabrication of tawdry empty stimuli which kill the receptivity of the soul.”

I’m listening.