Stop (Literally) Fast-Forwarding Your Life

Why speeding through is the slowest form of suicide.

My dear, here we must run as fast as we can, just to stay in place. And if you wish to go anywhere you must run twice as fast as that.

—Lewis Carroll

Yesterday is a cancelled check. Today is cash on the line. Tomorrow is a promissory note.

—Hank Stram

Above: You are using your remote control to read these very words. It’s not blue, just sleeker and made of glass.

When I first turned on Click, I thought I was sitting down to watch a comedy.

Adam Sandler equipped with a magic remote that fast-forwards past the boring parts of life? Count me in! It seemed like a perfect recipe for a cute, harmless cornball.

Almost ninety minutes later, I realized I’d actually watched a tragedy disguised as a family movie. A Trojan horse wrapped in slapstick.

Here’s one of very many clips that still haunt me:

It felt absurd then.

Now it feels like Tuesday.

Because the remote exists.

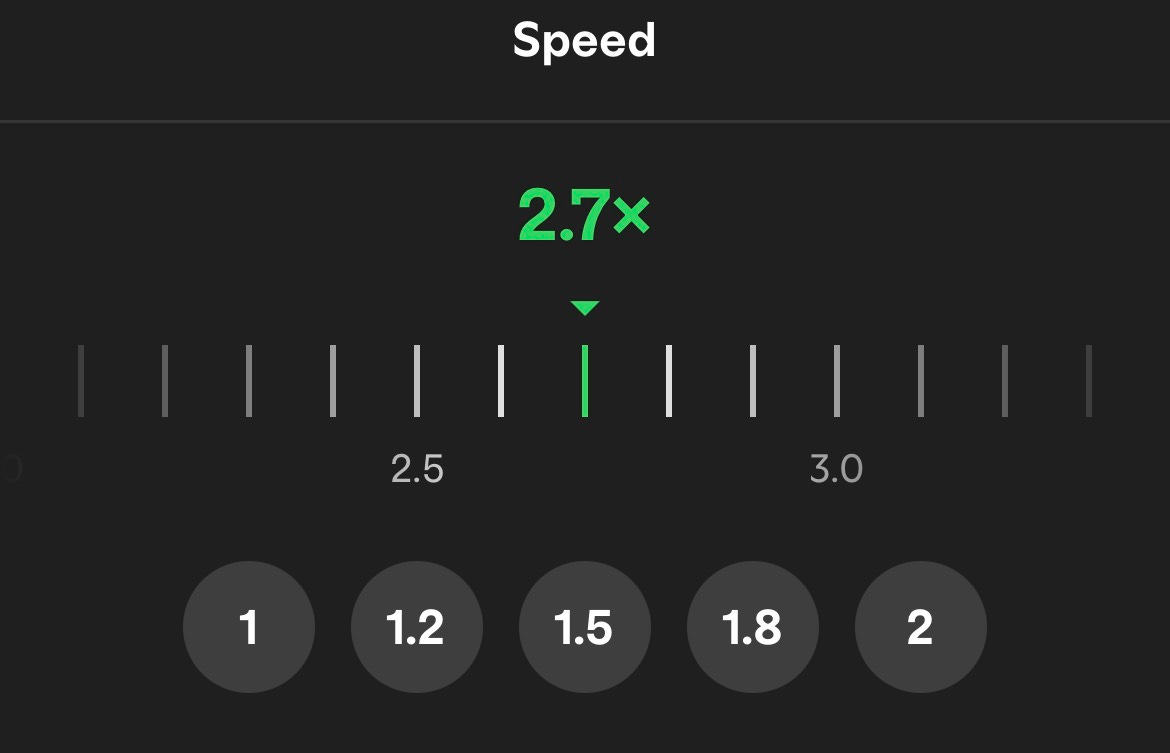

We call it 1.5x, 2x, 2.7x, 3x.

My Own Remote Control

I’ve noticed something embarrassing as of late.

When someone sends me a YouTube video or podcast and it’s five minutes or longer, something in my brain flinches.

I immediately try to speed through it, like I’m sprinting from the Grim Reaper.

1.5x. 2x, even 3x.

If I could go to 5x without losing comprehension, I probably would.

It’s the same with longer articles (hypocritical, I know).

If the scrollbar looks tiny—microscopic, like an elongated mitochondria—I “save it for later.” Ne’er to be seen again.

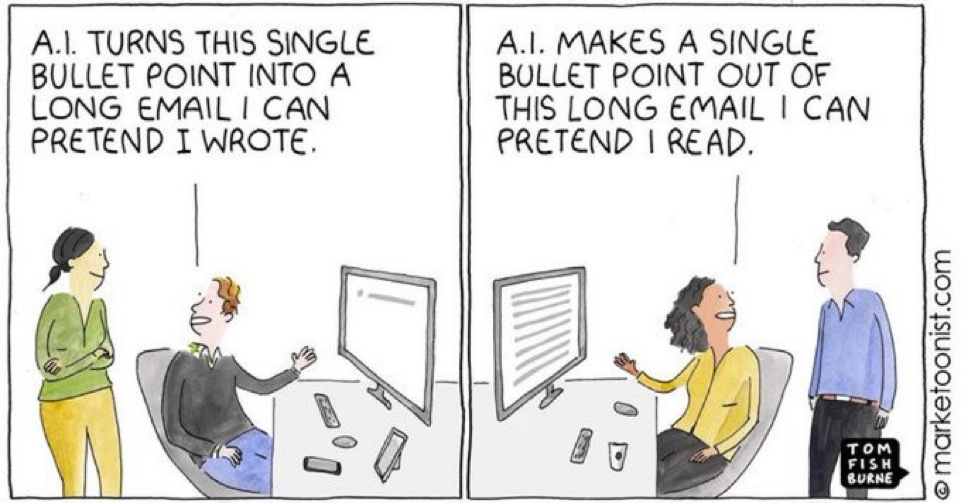

Instead, I almost instinctively open X for my informational fix, the jittery drip of edutainment, the slot-machine hit of half-insight, half-dopamine. Tiny pellets of “knowledge” stripped of context but optimized for my shortened attention span.

Why read the article when I can get the hot takes? Why suffer through the sentences when I can glean the snippets?

The problem is not that content has gotten longer.

It’s that I’ve gotten shorter.

My patience.

My presence.

My attention.

My soul’s willingness to sit inside a moment without trying to metabolize it like Joey Chestnut on the Fourth of July.

The Tyranny of Acceleration

We are living through a cultural tempo shift so enormous it barely registers as change.

The dial turns by itself now.

Human life used to have a natural pacing—seasonal, cyclical, attentional.

Now the pacing is algorithmic, optimized, accelerated.

Per Cathy O’Neil in Weapons of Math Destruction, our days are increasingly dictated by “models [that] encode human prejudice, misunderstanding, and bias into the software systems that increasingly manage our lives.”

This chart showing relative technological adoption should terrify us.

Not because AI is scary (though it’s off the rails in the opinion of this author), but because acceleration has become the default setting.

Society is speeding up faster.

Velocity is no longer the problem. Acceleration is.

The Soul Cannot Sprint Indefinitely

Philosopher and theologian Josef Pieper saw the future clearly from 1957.

In Happiness and Contemplation, his warning is not subtle:

[T]he greatest menace to our capacity for contemplation is the incessant fabrication of tawdry empty stimuli which kill the receptivity of the soul.

Kill the receptivity of the soul.

Not weaken.

Not diminish.

Kill.

There is a spiritual death in living life at 2x.

And Byung-Chul Han, prophet of The Burnout Society, diagnoses the inner mechanics of our acceleration-addiction with surgical precision:

The acceleration of contemporary life also plays a role in this lack of being. The society of laboring and achievement is not a free society. It generates new constraints. Ultimately, the dialectic of master and slave does not yield a society where everyone is free and capable of leisure, too. Rather, it leads to a society of work in which the master himself has become a laboring slave. In this society of compulsion, everyone carries a work camp inside. This labor camp is defined by the fact that one is simultaneously prisoner and guard, victim and perpetrator. One exploits oneself.

We are self-exploiting.

Self-accelerating.

Speeding through the very moments we will one day wish we could return to.

We are the inmate and the warden.

We are the burned-out worker and the boss demanding more.

And the boss always says: “Faster.”1

Abundance as Poison

Swiss physician Paracelsus wrote that the dose makes the poison.

Digital abundance sounds luxurious, but abundance without limit becomes a cancer.

Too much water drowns the seed.

Too much light bleaches the world.

Too much information erases understanding.

We try to “get through more”—but more turns us into skeletons wearing headphones, clicking “Next” until our soul crumples inward like a star collapsing into a black hole. Hungry for more until we devour ourselves.

We forget the original sin: Motion is not progress.

We forget the original miracle: Life is something to be lived, not completed.

We are Sandler in Click, furiously fast-forwarding through the boring parts—only to discover they were the parts with texture, meaning, friction, growth, presence, small joys, slow beauty.

We are treating life like a chore list instead of a miracle.

Trying to “get through” it like it’s a DMV form.

The overbearing, endless, exhausting “Yes” to more—doesn’t deprive us.

It saturates us.

It erodes us.

It exhausts us into oblivion.

We do not die from scarcity.

We die from surplus.

Charlie Munger was famous for saying, “All I want to know is where I’m going to die, so I’ll never go there.”

And yet, even he eventually reached the place he spent a lifetime avoiding.

We all do.

But he didn’t sprint.

He didn’t fast-forward.

He didn’t live on 2x to “get through more.”

We are the ones doing that.

We are the first culture in human history to accelerate toward the end of our lives on purpose—fast-forwarding, optimizing, compressing—rushing through the only non-renewable asset we possess: now.

And for what?

To arrive at death faster?

If the destination is guaranteed, maybe the only thing that ever mattered was the pace at which we walked there—slow enough to feel the air, slow enough to notice ourselves living, slow enough to actually be here.

Which brings me back to Click.

One of the things I found so clever as a kid was the Bed Bath & Beyond gag with the magical backroom staffed by a zany Christopher Walken

But now that I’m older, the joke lands differently.

There is no Beyond.

There is no secret aisle where time slows down and life finally begins.

There is only the unskippable present, the small unhurried seconds we keep sprinting past.

Yesterday is gone.

Tomorrow is a promise no one signed.

All we get—the only thing we ever get—is the here and the now and the chance to stop fast-forwarding long enough to actually live inside it.

Per my about page, White Noise is a work of experimentation. I view it as a sort of thinking aloud, a stress testing of my nascent ideas. Through it, I hope to sharpen my opinions against the whetstone of other people’s feedback, commentary, and input.

If you want to discuss any of the ideas or musings mentioned above or have any books, papers, or links that you think would be interesting to share on a future edition of White Noise, please reach out to me by replying to this email or following me on Twitter X.

With sincere gratitude,

Tom

I always joke that everyone wants to work for themselves until they realize the boss is a real jerk.

This article was too long.

KIDDING!!!

And it was weird, because Adam Sandler does not usually bring tears to my eyes.

Thanks for this.

You put into words something I’ve felt myself doing but never articulated. Thank you